The making of the Communion wafer is something most Catholics never think about. The wafers are everywhere, and just miraculously show up on the altar. And, it’s a mundane and simple process to make them. It involves heating a mixture of pure wheat flour and water – and nothing else – between two metal plates, which imprint a religious symbol on the face. But the market for communion hosts is a very competitive market, now largely supplied by one dominant secular company in Rhode Island.

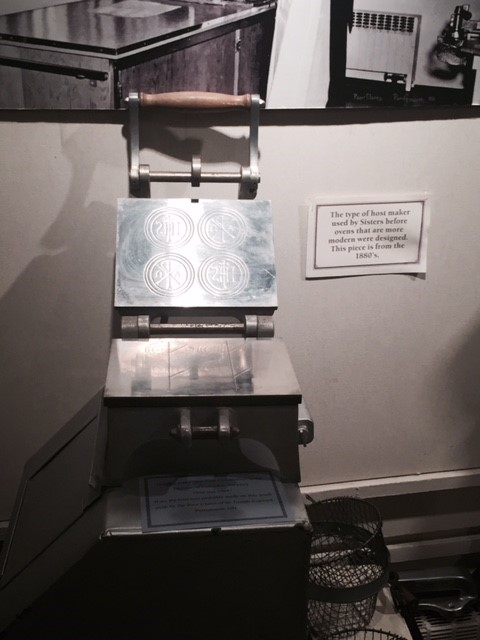

Even as early as the late 20th century, hosts were still made by priests, nuns, or parishioners for theirs or neighboring churches. The Jubilee Catholic Museum in Columbus, Ohio, has an old steam-heated host making machine from the 1880s, that was used by the Poor Clare’s of St. Joseph’s convent of Portsmouth, Ohio. That operation supplied hosts to the Diocese of Columbus and other Ohio dioceses.

An 1880s Communion Host machine from Portsmouth, Ohio.

Then came the council of Vatican II, which changed, among many things, the nature of the communion host. Before Vatican II, the hosts were much thinner than they are today, and meant to dissolve on the tongue, as that was how they were received at Communion. Vatican II, changed that and allowed parishioners to receive the host in their hands. It also allowed hosts to be thicker and taste more like bread. How to do this with just two ingredients is a miracle unto itself.

Growing up in the 1970s, my church in Cincinnati had parish bakers who made actual loaves of bread that were used at communion. I remember them being very inconsistent, depending on the baker. Some were chewy and very sweet, while others were somewhat bitter and not so tasty. The inconsistency in batches was probably one of the drivers for that practice being stopped.

Hosts fall into the same category in Europe as the anise-spiced springerle Christmas cookie – baked goods with images printed on them. In Germany, those baked goods are called bildergebaeck. Springerle is thought to have originated in the monasteries of southeastern Catholic Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Biblical images were very popular on springerle, so, this famous Christmas cookie is probably a secular offshoot of communion bread. Before the Nicene Council of 325, communion was celebrated with a full meal. The council limited the Communion celebration to bread and wine.

A similar Christmas tradition in the Catholic regions of Poland, Lithuania, and Slovakia, to springerle, involves a special communion-like thin host, called oplatek printed with a Christmas image, being passed around and broken at the family dinner on Christmas Eve.

One family owned company, Cavanaugh, in Greenville, Rhode Island, now supplies 80% of the hosts to U.S. Catholic Churches. In 1943, a local Jesuit priest in Greenville asked local Catholic inventor John Cavanaugh Sr., to invent a more-automated host making machine to help the nuns at this laborious job. Cavanaugh created ovens and mixers for the nuns; then three years later, John Jr. and his brother Paul started making bread themselves. There are still orders of nuns and parish bakers making hosts for churches in the U.S., but their numbers have decreased significantly in the last several decades. The equipment is very manual and the work taxing for aging nuns, clergy and parishioners.

Cavanaugh’s hosts range from simple printed image of the cross to elaborate images of a lamb. And, some say the Cavanaugh hosts break cleanly and have a nice bread flavor, not the pasty flavor of some of the religious-made hosts.

For Cavanaugh it seems to be a recession-proof business. Even during the U.S. economic downturn, their business was one of the only to increase. Apparently as the economy takes a nosedive, more people go to church.

Hosts for the Protestant denomination churches are made in a different area than those destined for Catholic churches, as the Protestant hosts include other ingredients like oil. And Cavanaugh has a similar market share to the U.S. in Australia, Canada and Britain. Where is the growth market for the communion host industry? It seems, West Africa.

The Benedictine Sisters of Perpetual Adoration in Clyde, Missouri, are the largest religious producers of communion hosts in the U.S. and can make up to 8 million wafers a month. But they can’t compete with Cavanaugh’s production capacity of up to 25 million wafers a week. The Benedictine Sisters became the first community to product a low-gluten altar bread that was approved by U.S. bishops in 2003, of which they sell 15,000 a week.

The only requirements for communion wafers is that they be unleavened, made purely of wheat (with no preservatives), recently made, so there is no danger of decomposition, and must have at least some gluten in them. The Vatican recently released a letter that hosts that are completely gluten free are “invalid matter for the celebration of the Eucharist.” If someone has celiac disease and can’t have any gluten, the U.S. Conference of Catholic bishops says that may receive a wine only communion. It is also important that they hosts be crumb free. You don’t want pieces of the transubstantiated Christ going everywhere. And, although it’s not a requirement that the manufacture must be human hands-free, Cavanaugh markets their products as hands free, saying it contributes to the spiritual nature and sanctity of the host. This plays to the pre-Vatican II conservative ideas of older clergy who were used to administering communion to mouth.

There is one local producer of communion hosts left. They are the cloistered Passionist Nuns in Erlanger, Kentucky on Donaldson Drive, who have been making hosts since 1951. The nuns who make the hosts change out of their black habits into light blue ones at 8:30 AM each morning and spend about six hours a day making hosts.

Sr. Mary Angela, a Passionist Nun from Erlanger, Kentucky, cuts the hosts with a foot operated drill from a larger 14″ host.

Their process starts with mixing the flour and water. One scoop of batter is ladled onto what looks like a waffle machine or pizzelle maker, which imprints the symbol of the chi-ro, an ancient symbol of Christ. The large host is cooked, the edges trimmed and is placed on a rack in the humidifier to cool and then be remoisturized over night. After being remoisturized – to avoid cracking during the final cutting – they are stacked 72 sheets high and then taken to a host cutting machine. The machine is foot operated and can cut 4500 hosts from one stack. The nuns will cut six stacks in a morning. The hosts are bagged and then ready for shipment. A day’s production for these Passionist nuns is about 27,000 hosts.

The cottage industry of nun- or parishioner-made communion hosts is on a steep decline and in huge competition to Cavanaugh. There may never be a return to hand made hosts or the birth of a ‘craft communion host’ market, but the making of them has a long tradition in the Church.

Pingback: Corpus Christi: Wafer vs. Bread - Stephen Morris, author

Hello I am responsible For the burial of several relatives and I would appreciate To know how I can purchase communion wafers so I can send to my relatives around the world with treasures that my relatives have Left Behind don’t wish for anything for myself and I would be very gracious and if you could help me Thank you so much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Communion wafers are not sold outside of the church

LikeLike