The former Sycamore Grange Hall on Kenwood Avenue in Blue Ash.

There’s an old building on Kenwood Avenue in Blue Ash, clad in aluminum siding, that hides a rich but long forgotten history of farmers in Hamilton County and Southwest Ohio. It blends into what is now a bustling business district and sits next to the wildly popular Blue Ash Chili Parlor. The Historic Hunt House Museum in Blue Ash has a note of it on an old map in their collection.

An early 20th century overhead image of the Hunt Farm in Blue Ash, the community that belonged to the Sycamore Grange.

But when it was built, the Sycamore Grange # 2307, was surrounded by farms, like that of the Hunt farm around the corner, built in 1861 by John Craig Hunt. John’s son , William and wife were members of the Grange.

Sycamore #2307 was part of the national Grange Movement, started in 1867 by Oliver Kelley, a member of the Department of Agriculture, as the Patrons of Husbandry. It was a secret society fashioned after the Masonic organization, but allowed women, and also promoted their right to vote. It’s mission was to develop the higher and better life of the rural farm communities in America. The isolation and lack of social and educational advantages made self interest and protection of farmers through the Grange a big point in the organization’s early recruitment.

The local Grange was a place to come for both men and women, and their children to socialize, discuss farm techniques, compare livestock and crops, have bake-offs, dances, farm dinners, quilting bees, and host literary readings and dramas. Members would pool their money together to buy communal plows and shared farm equipment. Granges also operated their own stores, which charged fairer prices than other retailers. They built community grain silos, avoiding the high costs charged by the railroads. It was one of the few totally secular community societies in America.

At first membership was limited only to farmers, but was then opened to others. The organization suffered a decline in the 1880s, as people became turned off by it being used as a political vehicle. The Grange experienced a brief rise in the turn of the last century, but it then quickly declined again. Ohio’s Grange organization actually accomplished something good, lobbying the state to enact a law regulating the rising railroad freight charges at 5 cents a mile for a ton of freight.

Cincinnati even hosted the Ohio Grange Convention in 1921 at the Hotel Sinton. At the time there were two Hamilton County Granges – Sycamore # 2307 (Blue Ash), and Crosby # 2194 (Harrison); four in Butler County – Fairfield # 2341 (now the Pomona Grange Butler County # 017), Hanover #2309, Collinsville # 2264, and Monroe #2160, now reformulated as Monroe # 2018; and two in Warren County – Mason #1680 and Lebanon #1462. Collinsville Grange is still very active, and the oldest continually operating Grange in Southwest Ohio, hosting a Butler County Bake-o-Rama at the Butler County fair.

The State of Kentucky has no actibe Grange organizations, but one farm community, Carthage, Kentucky, in Campbell County had a Grange organization, whose building is still standing.

There is one Grange Hall in the Cincinnati area still standing as such- the Mason Grange Hall # 1680 in downtown historic Mason. As there are no longer any active Grange organizations in Hamilton County, it doesn’t function as a society, but is used as sort of a community center, housing events like Empty Bowls, a local charity event. The Mason Grange was started as Mason Grange # 49, Patrons of Husbandry, on May 10 1873, by S. H. Ellis, who was then the Master of the Ohio State Grange, and who had founded the first grange in the area in Springboro, Ohio, on October 1, 1872. Red Lion Grange # 8 followed shortly in 1873, in Red Lion, Ohio, south of Springboro, with John Gustin as Master, and local Poland China hog breeder of the Maple Lane Herd, William N. Robison, as secretary. Other granges popped up in the same year in hamlets of Utica and Ridgeville, Ohio, a few miles northwest of Red Lion, in Warren County.

To the east of Cincinnati, in Crosby Township was the Crosby Grange # 2194, which had its beginnings as the Sand Hill Grange in Harrison, on the property of Hammand and Emiline Roudebush at Kilby Road.

Probably the best surviving legacy of the Grange in our state are the Ohio Grange Cookbooks that have been published in small runs since the 1930s. They’ve become very much collector’s items for foodies, and house priceless historic Ohio farm recipes and farm remedies. The 1938 Ohio Grange Cookbook has a recipe for wallpaper remover (vinegar, engine oil, flour, salt and ammonia). It also instructs how to measure the temperature of these new fangled gas stoves, by seeing how long it takes to brown flour on a pie pan.

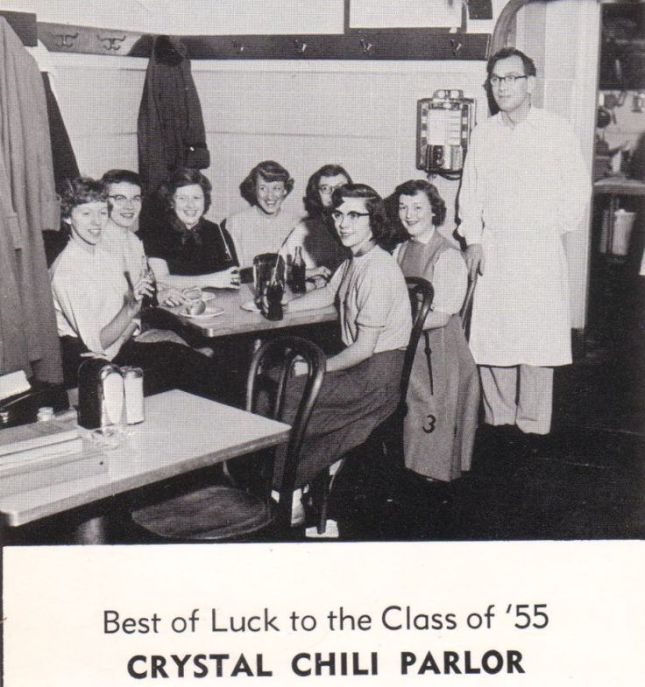

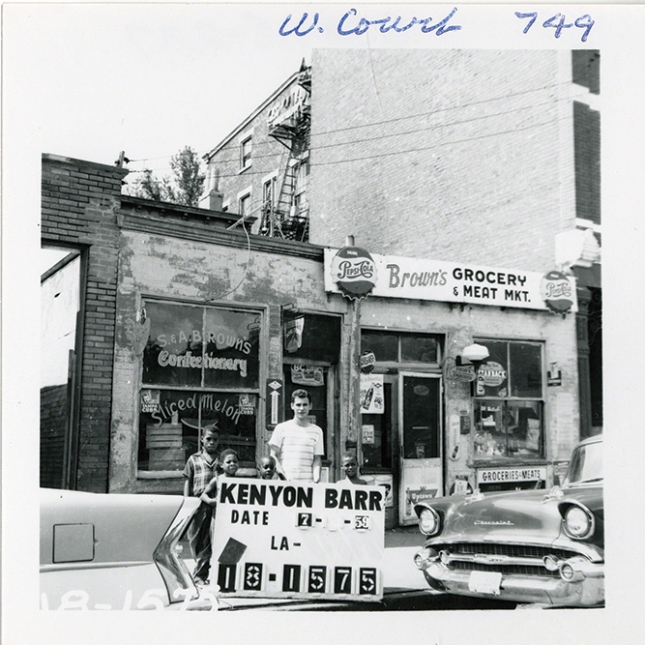

Before Cincinnati razed the entire Kenyon-Barr West End neighborhood in 1956 in the name of Urban Renewal, they took pics of the wonderful buildings and businesses. These young boys proudly stand behind the photo marker in front of their neighborhood grocery and confectioner, not knowing that they will be deported from their homes a few months later.

Before Cincinnati razed the entire Kenyon-Barr West End neighborhood in 1956 in the name of Urban Renewal, they took pics of the wonderful buildings and businesses. These young boys proudly stand behind the photo marker in front of their neighborhood grocery and confectioner, not knowing that they will be deported from their homes a few months later.