Over the weekend I went to a bottle collectors’ show in Northern Kentucky. There were anything from vintage cola bottles to ancient apothecary jars and containers. But being in Greater Cincinnati, one of the things I saw a great deal of were Jumbo Peanut Butter jars. It seemed like those from nearly every era since its introduction to the market in 1906 were on display.

Jumbo Peanut Butter was a product of our own Frank Tea and Spice Company, founded in 1896 by immigrant brothers Jacob, Emil, and Charles.

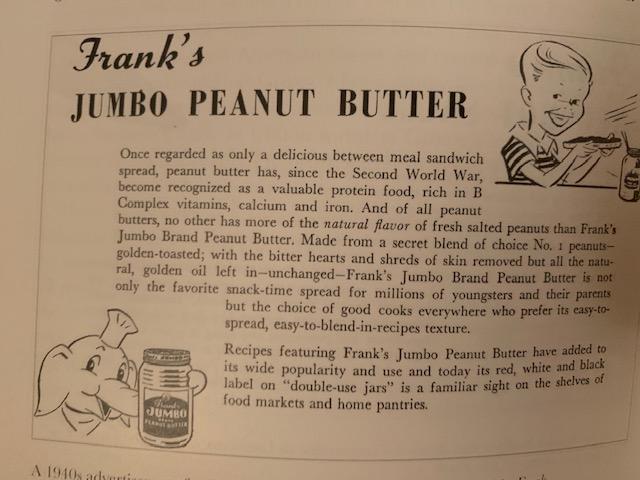

Frank is more famous for introducing their Frank’s Red Hot Sauce, that became part of the recipe for the original Buffalo Wings Sauce. It was made from a blend of choice # 1 peanuts, golden roasted with the bitter hearts and skin removed. It wasn’t homogenized creamy peanut butter as we know it today, it was the kind with the oil on top, with the puree below. You had to mix it yourself before spreading.

It was part of a trend of food and other household products named after Jumbo the Circus elephant, who was bought from the London Zoo in 1882 and died shortly after in a railroad accident in 1885. Although he didn’t last long in life, his skeleton was schlepped around by Barnum and Bailey for the next 20 or so years, an indication of his popularity. Today, Jumbo’s skeleton is at the Museum of Natural History in NYC. And, many folks collect the products his image dons, like our Jumbo Peanut Butter.

The funny thing is that peanuts are not part of an elephants diet, but they were popular at circuses where elephants performed, so they were a ready and cheap supply of food.

John Harvey Kellogg of the cereal company applied for the first patent in America for nut butter made from peanuts or almonds, and by 1896 Kellogg was making it on a small scale. The 1904 St. Louis Worlds Fair catapulted peanut butter into the national spotlight and by 1922 there were enough commercial manufacturers to justify the formation of a National Peanut Butter Manufacturer’s Association. But according to a 1940s Frank Tea and Spice Company brochure, it wasn’t until World War II that it was given status as a between meal snack because of its high protein and Vitamin B, Iron and Calcium. Anyone outside of America, like the Europeans do not get peanut butter. They have another nut butter Nutella, made of hazelnuts and chocolate blended together.

Female workers packing peanut butter at Franks in the 1940s.

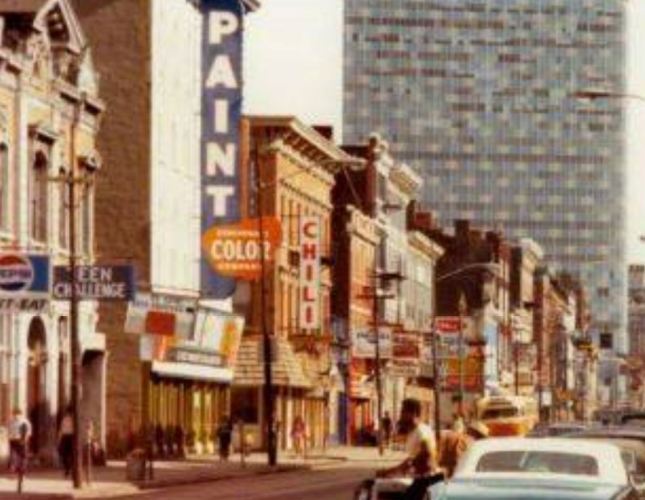

Frank applied for a patent on Jumbo in 1927. They built a new plant at Third and Culver Streets, and then in 1920 a building at Fifth and Culvert Street was built with equipment for the cleaning, inspection , roasting and grinding of peanuts and the packaging of the peanut butter. Can you imagine how great the neighborhood smelled when they were roasting the peanuts?

In the 1940s for a brief time, Frank also made a Jumbo Apple Butter in Cincinnati.

They made it in a variety of jara – the most common being the 1 lb. But they also made small sample sizes shaped like Dumbo, and a large family sized octagonal jar. Jumbo Peanut Butter was also known for the eclectic sayings on the bottom of the jars including “Try Jumbo Peanut Butter Sandwiches”, “Best for the kiddies”, or “Jumbo Good Enuf for Me”.

Frank Tea and Spice was sold to a national company in 1969. According to John Frank, the grandson of the founder and last owner of the company, Skippy approached them to toll manufacture their homogenized spreadable peanut butter. But Frank Tea and Spice refused because they didn’t have the money to invest in homogenization equipment. Skippy found another manufacturer and they and other brands like Peter Pan took over they market with their homogenized spreadable peanut butters. And, Jumbo Peanut Butter became a beloved brand of the past, whose jars are now widely collected.