Why did we replace the wonderful rolls our Germanic immigrants brought along on their transatlantic voyages in favor of the commercialized American white buns? For way too long we’ve settled for the flavorless, industrially produced white bun for our hamburgers and other meat sandwiches. As the ‘better burger craze’ increases momentum, higher quality buns are being brought out to the forefront. The brioche bun, and even the pretzel bun are some of these upscale buns. But none of them compare to the American bun’s European ancestor.

If we just go back a little bit in time, we find something called the brötchen. It’s still a daily staple today in Germany. The brötchen has been around for centuries, and is the ancestor of our American burger bun. The hamburger itself, the largest user of our American bun, is named after a German port city favorite, the Hamburg steak. It was a ground meat patty that was chopped and cooked. Hamburg, before the turn of the 19th century was known for its minced and chopped beef, a method borrowed from the Russians by German butchers. Our term hamburger was a derivation of this product. This minced German product looked more like the Salisbury steak than today’s hamburger.

Today, a burger-like product called frikadellen, is popular in Germany. They look like mini, slider-sized burger patties, and wedge perfectly into their brötchen. I imagine as the Hamburg steak moved from the bierstube to the street vendor, it took on this smaller, frikadellen sized form, and was sandwiched between a brötchen, for the convenience of the rowdy sailors who ate them on the run.

The early history of the American hamburger is sordid for sure. There are at least six claimants of its invention. The bottom line is the hamburger likely appeared in the late 19th or early 20th century. And, it was designed to meet the demand of a rapidly changing, industrialized society who had less time to cook for themselves. That’s the genesis of a lot of other American convenience foods like the coney.

The brötchen, meaning literally, ‘little bread’, is an everyday bun. In Germany you can get them for under 20 cents, fresh-baked everywhere – in bakeries, supermarkets, and even gas stations. It’s a bit smaller than our American hamburger bun, like most portions in Europe. We should take lesson from their smaller portions! A brötchen is deliciously crispy on the outside, and fluffy and chewy on the inside. The secret to a good brötchen is the egg white wash, and baking at a high temperature with steam.

Whenever I’ve travelled to Germany or Austria I’ve always loved the fresh brötchen served with homemade marmalades, cheeses, and cold cuts at breakfast in every hotel. You might even add a sliced egg, tomato or cucumber. One over-the-top hotel breakfast in Vienna I experienced had an entire bar dedicated with fillings for their brötchen. Katharina’s in Newport, Kentucky, serves this traditional German breakfast with brötchen. It’s just like I remember in Germany.

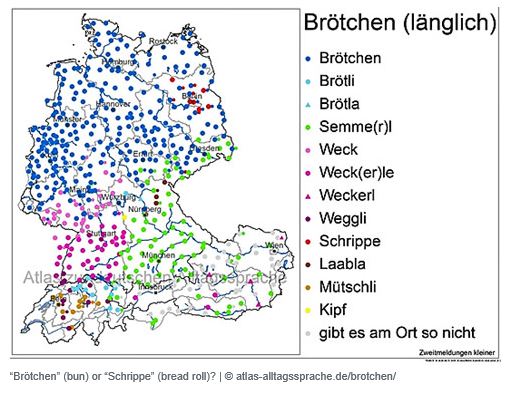

Every region of Germany has their own name and version of the brötchen. They can vary in spice, type of flour – wheat, spelt or rye – and toppings. Munich has its semmel, which could house a thick slice of leberkase or liver pate. What’s schrippe to a Berliner is weck or weckerle to a Swabian in Stuttgart. Schleswig-Holstein and Hamburg have their rundstuck – literally ‘round piece’, which could sandwich a frikadellen. In the Baltic Islands and Mecklenburg, they’re called bömmel, which means ‘bauble.’ The doppelweck or ‘double bun’ is a Saarland specialty which consists of two rolls joined together side-by-side before baking. The Black Forest has its mutschli and Franconia has its kipf. Even the elevated bun we call a kaiser roll in the U.S. is really a wannabe kaisersemmel, a type of brötchen from Bavaria and Austria. It’s named after the Kaiser because the top has centrally cascading-out folds that resemble an imperial crown.

In U.S. foodservice there’s a several million dollar industry supplying bun warmers, toasters, and buttering machines. This is ensure substandard commercially baked buns are somewhat good when served with its burger patty. You’d be surprised at the high sugar content in the typical fast food bun. So why didn’t we just keep a great bun to start with that doesn’t need all this fuss?

I think we can blame our sinful conversion to the American bun on a German immigrant, H. J. Heinz, the condiment king. He sold us a bill of goods that all our sandwiches require oozing heaps of ketchup, relish, and mustard. His evil empire taught us that our sandwiches needed to be messy to be good. We Americans do love our messy loose meat sandwiches. Our barbecue, sloppy joes, and plethora of messy burger toppings need to be eaten with care. A crispy-on-the-outside bun like the German brötchen, just didn’t lend itself to our eat-on-the-go, convenience lifestyle, with these messy sandwiches. One bite through the crusty outside of a brötchen and plop goes a drop of messy on your business suit. So we took the lovely brötchen and degraded it into a soft white bun that didn’t provoke that plop. We kept the sesames on top to keep a bit of pizzazz – but that didn’t totally absolve our sin.

Germans don’t really eat any messy meat sandwiches. Brötchen are served at breakfast to sandwich their wonderful regional cold cut meats and sausages, or their beautiful marmalades and spreads.

A basket of weissenbrotchen.

The most iconic American bun, the sesame- seed topped one bears familial resemblance to the German weissenbrötchen, which can have sunflower, sesame or poppy seeds on them. This connection to me is DNA evidence that our American hamburger bun is a descendant of the German brötchen. Even though the sesame seed brought to America by the West African slaves trafficked to Georgia and South Carolina much earlier in the 1600s, there’s no evidence they used it as a bread or roll topper. Germans had been importing their sesame seeds through Syria and the Middle East, not Western Africa. I think the first burger chain that comes out with a ‘Brötchen Burger’ will really set themselves apart in the upscale bun market. For me the new food slogan should not be, “Where’s the Beef?” but rather “Bring Back the Brötchen!”