Historians love a character and I found one in Uncle Joe Siefert, an German immigrant who was one of our most interesting growers of the Ives Grape. If there were a German Page 6 of the Cincinnati Enquirer, Uncle Joe would be in it every week. People would have asked “What did Uncle Joe do this weekend?” If there was a party people would ask, “Was Uncle Joe there?’ Joe was a big man – and by big I mean over 300 pounds – and a Renaissance man. He was a civic-minded, family man who served in public office, a philanthropist and fundraiser, a joiner of clubs and organizations, a winegrower and winemaker, and a good friend and a hardy partier.

The cool thing about Joe in relation to Cincinnati wine is that he exhibits both the early days of it, and the latter days. Although Joseph Seifert (1810-1894) grew up in Baden-Wurtemburg wine country in the town of Ettinburg, in Waldburg, about 6 miles from the Rhine River, he wasn’t a winemaker by trade. His dad had been a gunsmith, but died at an early age and Joe was apprenticed to a stone mason at age 11. A few years later he was drafted into the army, where he served 3 years, before escaping to the U.S. He landed in Baltimore, then walked to Pittsburgh, then to Wheeling, Virginia (no West at that time) and then to Cincinnati where he arrived with only $4 in his pocket. That same day Joe got a job as a mason, and a year later he had his own contracting company with over 150 German stonemasons working for him. It was during this contracting that he earned the nicknames “Uncle Joe” and “Honest Old Joe.”

We see the amazing lager cellars and beer tunnels of our city and wonder what type of men built these amazing structures before power tools and backhoes. It was Uncle Joe and his crews of sturdy Germanic men. Starting in 1847, Joe and his crew built some amazing structures in Cincinnati including Nicholas Longworth’s Wine House on the hill leading up to Mt. Adams. The extensive structure had three subbasement cellars and was four stories tall above ground. Joe also built the first pretzel oven in the city, the old Mayor’s Office at Hammond and 4th streets, the first three gas tanks for the city, the Little Miami Train Depot, and many other buildings.

Joe and his wife Elizabeth Brossner and their ten children lived in Cincinnati’s 10th ward on 12th street. But they also owned a 65 acre farm in the northwest Cincinnati’s Germanic farm hamlet of Weisenburgh, which would be renamed Monfort Heights. Many other German winegrowers like Charles Reemelin, had a house in the city and a farm in the West Side. The Siefert’s farm was at the corner of Burnt School Road (later renamed Cheviot Road) and Lincoln Avenue. On this farm, Joe had a vineyard of Catawba, Ives, Concord, and Minor’s seedling grapes, and a grove of plum trees imported from Germany. When he hosted the Cincinnati winemakers Association at his Monfort Heights farm in 1871, they commented how healthy his vines, especially his Catawbas looked that season. This is significant since most of the Catawba growers in Cincinnati had experienced major rot and failure in 1863 and many gave up or pulled up their Catawbas for other grapes. So, this indicates Joe had a pretty good working knowledge of grape growing. The fact that he was growing Ives, Concord and Minor’s seedling grapes, which were newer more resistant grapes appropriate for weird Cincinnati weather, also indicates he was tuned into the times and was in-it-to-win-it in local winemaking. The majority of other Ives growers were in Indian Hill, Madisonville, and Plainville on the East Side of Cincinnati, so Joe was the furthest grower of Ives in Greater Cincinnati.

When Nicholas Longworth told Joe he would give away the best farm in Cincinnati to whomever came up with a pesticide to cure mold on plum trees , his son Charles, also a big man weighing in at over 300 pounds, began experimenting to find the cure. He spent 12 years perfecting a cure for this curcullo, which included syringing the trees with a drugged liquid and dusting the foliage via a poled-sieve with superphospahte. He would write a pamphlet about this method. But Charles would inherit the best and most prolific farm in Cincinnati, anyway, his father’s which he would work on over 65 years.

Joe was famous for a cocktail he invented which he called “lemonade without water.” It was a sweetened combination of lemon juice, lemon peel and his own house made Ives wine as the “water” which he apparently carried around with him to events and shared with whomever would drink it with him. This was mentioned in Cincinnati papers more than just a couple of times. Maybe this was the secret tonic for Joe’s longevity as he lived to be 80 in a time where the average lifespan of a man was much fewer years. Joe was a carrier of German ‘gemutlichkeit’ wherever he went. Making Ives wine was tricky because the grapes turned purple five weeks before they were actually ripe enough for wine. If you picked them too early and made wine, the result would be super sour and acidic. When you waited the proper time they made a mild but flavorful acidic white wine similar to a German Riesling, that could be fortified or sweetened.

Uncle Joe really served his community. During the Civil War when poor men were being drafted against their will, he raised $11,000 in a day to save the men in his ward who needed to work to support their families. But during the Kirby Smith raid he was Captain for a local volunteer militia company.

Uncle Joe Seifert has a long list of other civil service. He was City Councilman for the 10th ward for nine years and was suggested to run for mayor because of his popularity. He was a member of the Humane Society, the Director for Longview Asylum for 7 years, a member of the Soldier’s Relief Fund, President of the German Pioneer Society, member of the City Infirmary Board and the Chairman of the sewage commission. He was an active member of St. James Catholic Church in White Oak, where he was buried, of the Cincinnati Horticultural Society and the American Winegrowers Association, formed in Cincinnati.

Another interesting story appeared in the Cincinnati Enquirer in 1884. It appears Joe’s house was right across the street from a bordello run by three local Germanic prostitutes, Lena Meyer, Emma Kister, and Sophia Lister.

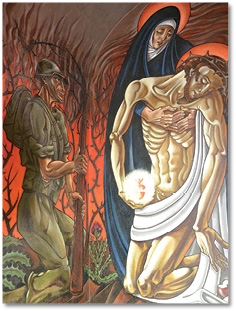

He and his family are buried under a monument written in German script and the anchor symbol of the Sacred Heart in St. James White Oak’s German cemetery section.