Frisch’s and Busken can have their pumpkin pies and their pie wars. Both are now different than their originals and commissary made, which means they’re not hand crafted. But there is one pie that rises above them all- still made after over 70 years only one day a year in the little village suburb of Glendale. If you don’t get a reservation before 5 PM at the Grande Finale, aptly named for its decadent desserts, they may run out of this delectable pumpkin pie.

For the last half dozen or more years my parents and I have had Thanksgiving dinner at Grande Finale. We congregate with the my sister and brothers’ families on the weekend. Virginia greets and seats us at a table in the Cabernet Room with a lovely view of the interior brick New Orleans style courtyard. This year, we got to sit in the main dining room with a great view of the entire restaurant.

We’re the weird table that gets the salmon and asparagus, not the turkey, steak or chateaubriand, like almost everyone else. I usually accompany the salmon with one of their amazing mushroom crepes. But the main event for us is really the pumpkin pie at the end.

The pie is served in a casserole dish with the crust is baked in. It’s a deep brown color, not some unnatural traffic cone orange as most others. Like the large size of its other desserts, Grande Finale’s pumpkin pie is about the size of maybe a third of a normal sized pumpkin pie. We usually order two for the three of us and end up packing some up for take home.

This pie is spiced traditional – it’s clove and mace forward, with cinnamon being the third fiddle. If there’s ginger, its not detectable, but might hold up the background for the deep old fashioned pumpkin pie flavor. The mild hint of cinnamon is in contrast to today’s cinnamon forward pumpkin pies you’ll find at the grocery. It’s not too sweet, so you can also really taste the pumpkin. Consistency is good – more dense than a custard, but still springy and delicious.

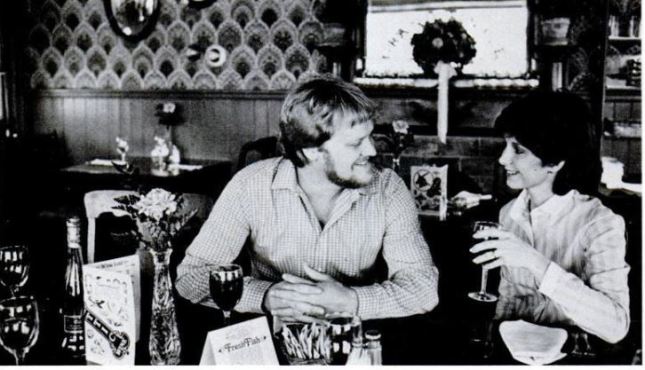

The recipe comes from Mo Youse, the mother of the original owner, Larry Youse, who opened the restaurant in 1975 with his wife, graphic artist Cindy. Even though the Youse’s retired in 2006 from the restaurant, the team that took over still makes this legacy recipe pie in homage of the mother of the man who built the restaurant icon still going strong after nearly 50 years.

Larry and Cindy Youse shortly after opening the Grande Finale.

Gary and Cindy grew up in Indianapolis and were classmates since Kindergarten. They fell in love in gradeschool, dated while attending Arlington high school, married after college, and had their son Zachary 18 years later. Wedged in between there was the founding and building of their restaurant, which they passed on in 2006 to retire to Vail Colorado. The couple restored the dilapidated Kelly General Store, built in 1850, with a nod to the historic. The main bar was a find from Germantown, Ohio, and the back bar is from an old Hyde Park Barber Shop. They also decorated it with fine oil paintings, the media in which Cindy still paints today in her Vail garden. At the restaurant, they became famous for their over-the-top desserts, their crepes, and their high class funkiness where a crepe could be devoured while listening to Ricky Lee Jones.

So once a year on Thanksgiving, we look forward to the best pie in town, Mo’s Pumpkin Pie, from an unassuming housewife from Indianapolis.