It’s always hard to pinpoint who invented a dish. The Weil, Schimmel, and Kulakofsky families still fight over which one of their ancestors invented the Reuben sandwich almost 100 years ago. Skyline Chili didn’t invent Cincinnati Chili, which many Cincinnatians think because they have the most parlors – Empress Chili was the first. And, there’s always the case with a business still around who claims they invented it, because the original business is no longer there to defend themselves. That’s the case with our Opera Cream. Papas in Covington, Kentucky, claims their ancestor invented it, but it was clearly invented decades earlier than they even were incorporated, by Robert Putman.

Aglamesis Nectar Ice Cream Soda.

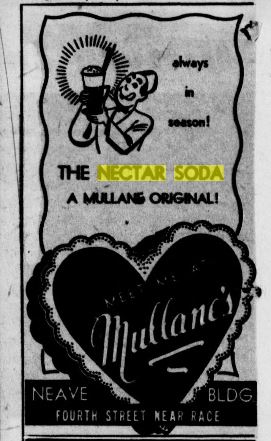

Such is also the case with the Cincinnati Nectar Soda. Many attribute Aglamesis with its invention, but it was invented several decades earlier by John Mullane at his confectionery and soda fountain on Fourth Street by 1892. Graeter’s Ice Cream stores, and all United Dairy Farmers ice cream counters also serve this legacy Cincinnati soda.

Now to be clear the nectar soda that we are talking about is the one flavored with vanilla and bitter almond, with a light pink color. It’s described as tasting like poundcake. There’s also a nectar flavor masquerading as the original, which is a tutti-frutti flavor, with cherry, pineapple, and citrus, and sometimes strawberry. But this is not the original nectar soda.

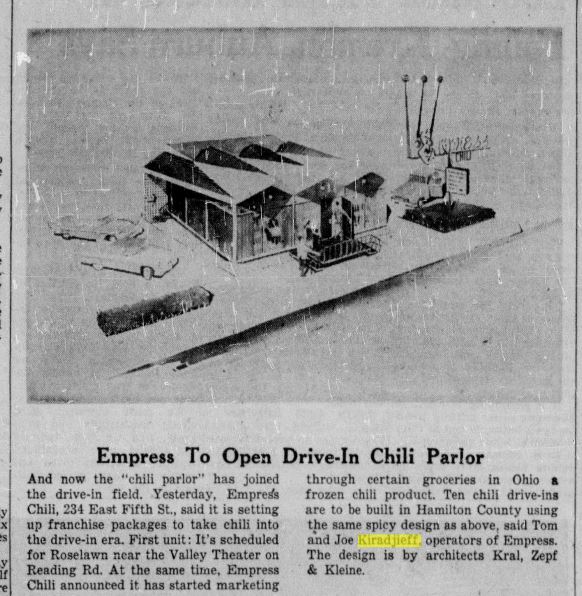

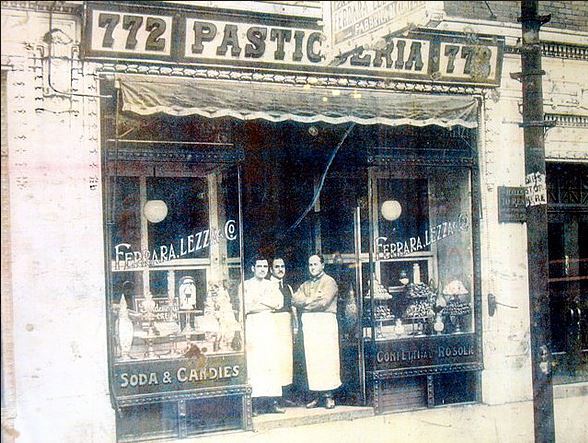

John Mullane and an ad for his Original Nectar Soda.

Although the nectar soda is becoming more obscure, it has been a continuously offered and celebrated soda flavor since 1892. In addition to Mullane’s, Dow Drugs, which used to have numerous soda fountains throughout Cincinnati, was a popular place to have one. The Cincinnati Club made their own nectar flavored sherbet. Fannie Hurst, an author raised in Hamilton, Ohio, immortalized the Cincinnati Nectar Soda in her 1931 romance novel Backstreet. The Cincinnati nectar soda was also mentioned in the 1931 Women’s Home Companion.

But, New Orleans claims THEY invented the flavor. In 1866, Isaac Lyons, a native of South Carolina, moved to New Orleans and went into the wholesale drug business. He began selling his nectar syrup to K & B Drugstores in the 1880s, who made it into nectar sodas, nectar cream sodas, and nectar ice cream sodas at their fountains. As in Cincinnati, this became a very popular flavor and other drugstores – Schweighardt’s, Bradley’s, Berner’s, and Walgreen’s – bought the syrup from Lyons and served this flavor. By the turn of the 20th century nectar sodas were a signature flavor of New Orleans.

The flavor expanded out into Cajun country to the sugar cane growing parishes along the Mississippi River like St. James. These Cajuns took the nectar syrup and mixed it with sweetened condensed milk to make a drink they call “Ping-Pong,” which is still served at holiday parties.

But, unlike Cincinnati, New Orleans’ nectar soda had a falling out in the 1960s, as drugstore soda fountains disappeared, and it’s only recently had a small resurgence. During that time until recently, the New Orleans nectar flavor moved from the soda fountain to the street snowball stand. Now about the only place you can get it in New Orleans as an ice cream soda is the American Sector café at the new World War II Museum. A few other places you can also get it are the Creole Creamery, and in a snowball at Plum Street Snowballs. There’s even a bakery that makes a nectar flavored King Cake for Mardi Gras season – Gracious Bakery. The flavor is billed as “Mardi Gras in Your Mouth.”

Rewind to Cincinnati’s nectar origin. Mullane’s Confectionery claimed the origin of the nectar soda, which they started serving in 1892, when they opened their deluxe soda fountain on 4th Street, in what was called “Cincinnati’s most fashionable block.” John’s mother, Mary Mullane, sent him to Quebec City Canada for a year from 1875 to 1876 to study the art of confectionery with William McWilliams, a prominent candy maker, who was Chief Confectioner to the Governor General of Canada. Mullane brought back the nectar flavor to his candy shop and made it into a hard drop candy, which he served from then on, along with a later nectar taffy, and then his later nectar ice cream sodas. A candy company called Lofty Pursuits in Tallahassee, Florida, still makes Mullane’s nectar drop candy from the original 1870s die they purchased from a descendant.

And, there is a legacy of nectar sodas in that area of Quebec City today, which leads me to believe that Mullane did learn the nectar flavor formula during his time at McWilliam’s shop. Cott’s and Allan’s made a nectar soda in Quebec. IGA makes a house nectar soda only in Canada, as did the Crush soda company. And Red Champagne, a Montreal soft drink maker, also makes a nectar soda.

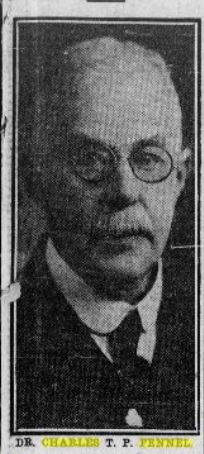

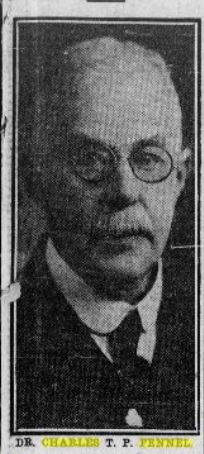

Dr. Charles Fennel, a pharmacist given credit in Cincinnati to inventing the nectar syrup.

However, an 1899 book of memoirs of Daniel Drake, an early Cincinnati physician, gives credit of the invention of nectar syrup to a pharmacist named C. Augustus Smith, who had a pharmacy on Fourth and Race Street in the 1860s downtown. But, a 1947 Enquirer article, the widow of Adolph Fennel II, credits her husband, who experimented with bitter almond and cream, and her father-in-law, Charles Fennel, who had a pharmacy at 8th and Race Streets with inventing it ‘ very early’. Charles’ father, Adolph Fennel Sr., a German immigrant who had a pharmacy in the 1850s and 1860s at 8th and Vine Streets, was also a prominent pharmacist who helped start the UC College of Pharmacy, and was the local chemist for the U.S. Food and Dairy Association, a predecessor to the FDA.

However, neither of these two Cincinnati pharmacists ever had a business that sold nectar syrup on a commercial scale. And, Mullane made their own syrup. In research for my Cincinnati Candy book, I obtained a copy of the original Mullane Nectar soda from descendants of John Mullane, which includes the ratio of bitter almond to vanilla flavoring.

Earlier references to the syrup appear in an 1858 newspaper of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which says William Bogel had “a delicious nectar syrup, which surpasses anything in the syrup line we have ever tasted.” And, a July 1857 Sandusky Ohio Register paper promoted Soda with Nectar Syrup by Adams & Fay’s Drugstores. But neither article described how the nectar syrup was flavored, which could have been the tutti frutti variety not the vanilla-bitter almond.

The Cincinnati nectar flavor travelled. One confectioner took it to Richmond, Indiana, and opened up Finney’s Confections. And, William Wright, a one-time worker at Graeter’s Ice Cream Parlor at Peeble’s Corner in Walnut Hills, opened a chain of ice cream parlors in Los Angeles in the 1940s. He took the nectar flavor he learned at Graeter’s with him. He tried to hide where he had stolen it from by calling it New Orleans Nectar. Marilyn Monroe was a fan of Wil Wright’s hot fudge sundaes.

In 1999 a woman names Susan Dunham decided to revive Nectar Soda on a commercial basis, and became president of the Nectar Soda Company in Mandeville, Louisiana, after having tracked down the recipe from some of Lyons’ ancestors. Sydney J. Besthoff of K & B drug stores was delighted with the news but, sadly, Dunham died October 24, 2012, at age 58, and the company died with her.

Today, a Nectar Soda Ice Cream is available in supermarkets, produced by the New Orleans Ice Cream Company.

There may be a connection between New Orleans and Cincinnati with the nectar flavor. The area of Quebec City, where Mullane first learned the nectar flavor, was known as a refuge for the Acadians who were expelled from Canada in the 1750s. The area of the Carolinas, where Lyons was from, and Louisiana, were both refuge to these dispelled Acadians, who became known as the Cajuns. So, I have a suspicion that this mixture of bitter almond and vanilla was originally a French Acadian flavor that made its way into the foodways of both New Orleans and Cincinnati.

So why the weird pink color? Well, while the blossom of the almond is white, the blossom of the bitter almond is pink.

While we can’t pinpoint when and who first invented nectar flavor, we can debunk New Orleans in saying that the flavor is exclusive to the Crescent City. We do know that trade magazines advertised soda fountain syrups across the country. It appears that both cities started serving it about the same time – sometime in the 1870s and 1880s, when soda fountains became popular, but Mullane’s popularized it in Cincinnati, and Lyons in New Orleans. And, Cincinnati’s has had a continuous supply since the 1870s.