There is probably no more recognized Easter candy than the marshmallow peep. That delicious sugary coated marshmallow confection can be eaten fresh, or made to sit out and get stale so it becomes delightfully crunchy. I’m a fan of the crunchy version. Local candy confectioner Aglamesis dips the bottom of the Peep in milk chocolate and calls them Muddy Chics. Sweet Tooth across the river completely coats them in chocolate. The other local candy that is associated with Easter is our Opera Cream, which comes in eggs, crosses, and now bunnies.

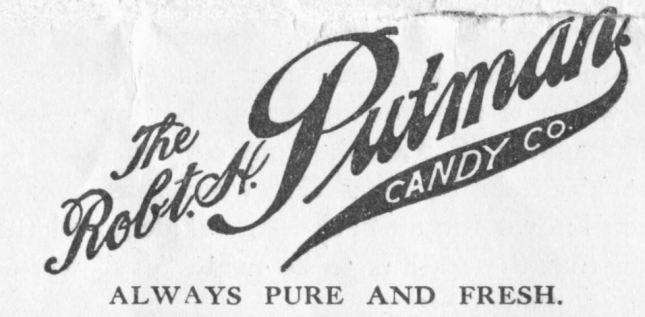

The man credited with the Peep’s invention, Roscoe E. Rodda, stirred up big controversy in the Cincinnati and national candy industries, as he made his way through co-ownership and merger of four Cincinnati candy companies. While in Cincinnati, he made partners with the inventor of our Opera Cream candy, Robert Hiner Putman, and may have divulged that secret recipe to a religious cult in Illinois, of which both were members.

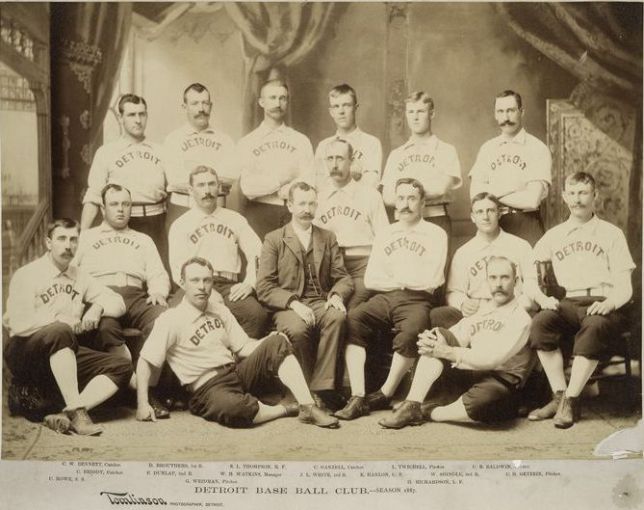

Rodda got his start in the candy business working in Detroit, Michigan, for the firm of Gray, Toynton and Fox. He married Luelle Chetham in Illinois in 1885 and made his way to Cincinnati, by 1891, listed in the city directory as a confectioner. He was in a good spot for the candy industry. At that time, Cincinnati was the fifth largest candy producer in the nation, with several large manufacturers that distributed nationally.

All along the way, Rodda and Putman were both involved in a Progressive Era cult, known as the Catholic Christian Church of Zion. The cult was founded in Chicago in 1893 by a charismatic Scotsman named Dr. Alexander Dowie. What separated Dowie’s evangelism from the competition was his teachings on his divine healing powers. According to Dowie, in revelations given to him by God, sickness was a manifestation of sin and lack of faith. All followers needed to do to be healed was to ask for Dowie’s prayers. Dowie also preached clean living, free of smoking, drinking, dancing, eating pork and shellfish, but not, interestingly enough – candy. Other Progressive Era promotors of clean living, like Dr. Graham (of Graham cracker fame) blamed sugary sweets on teenager horniness, but not Dowie. Dowie started evangelizing in Chicago at tent like revival meetings near the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, and quickly acquired a substantial and wealthy Midwestern following, around Chicago, and in Cincinnati.

In 1900 he bought land to start a religious community about an hour north of Chicago near Lake Michigan to be called Zion, Illinois. Then in 1902, he convinced 10,000 of his congregants to settle on this 6600 acre plot of land he bought, to build a theocratic utopia free of sin, vice, class antagonism and poverty – an Anti-Chicago of sorts.

Dowie built himself an opulent three story mansion in the center of town called Shiloh House, and brought in thousands of other, mostly well-to-do people. He created a print shop, which published his religious magazine called Levels of Healing. Here he published his sermons and talked about his healing ministries. Zion would become one of the largest and most grandly conceived Utopian communities in modern America. Before he moved his wife, son and daughter into his new mansion, a tragedy befell them. His daughter was preparing for a date, and started a fire with her kerosene curling iron that ended up killing her. Dealing with the death caused a rift between Dowie and his wife and son, as the fledgling cult was just taking off. Some also believe it was this tragedy that sent Dowie into a spiral of dementia that caused his ousting by the community in 1906.

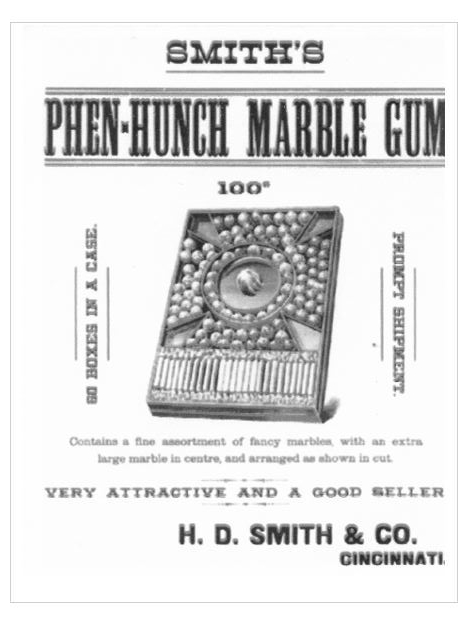

Zion was a hybrid of commune and company town. Dowie brought industries to Zion to support his socialist religious community. Settlers would work in various collectively owned light industries, which included a lace factory (that he brought experts from Scotland in for the startup), a candy factory, lumber mill and bakery. Everyone who lived there turned over their fortune to the city and all men were expected to work, and were given a profit at the end of the year.

Both Rodda and Putman were deacons of this Zion church in Cincinnati, which apparently had quite a number of followers. In the 1900 Level of Healing edition, Rodda praised Dr. Dowie’s healing prayers for his nine year old son, Emmons, who was hit by a streetcar in Cincinnati. Earlier he had credited Dowie’s healing prayers to restoring his daughter’s eyesight in 1897 at the Zion House in Chicago. Robert Putman, also praised Dowie in for his prayers saving his peach trees from blight.

In 1902 the Cincinnati Enquirer announced that Rodda, former operations manager of the Peter Eckert Candy Plant in Cincinnati was moving to Zion, Illinois, in May, to run Dr. Dowie’s Sugar and Confectionery Association’s Candy Plant, being built. One of the candies that Rodda supervised making was Jimcrax, a line of marshmallow candies shaped like comic characters of the turn of the century. It was probably at Eckert’s that Rodda learned the art of marshmallow candy making that he would later apply to his innovative Peep.

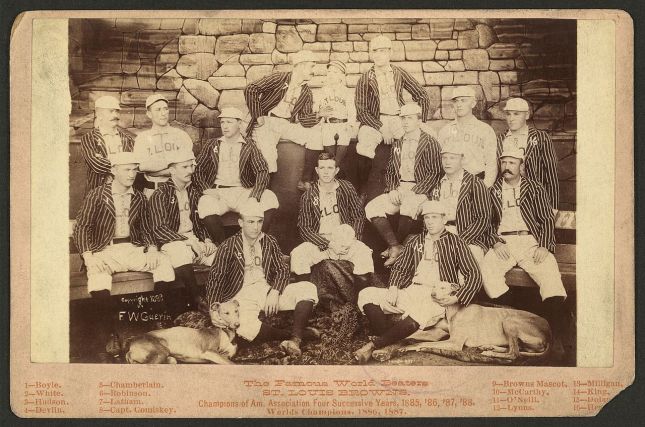

The Eckert Company would join the National Candy Company later that year in September, an association of 12 other candy companies in St. Louis, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other large candy manufacturing cities. This is perhaps the reason that Rodda left town for Zion before the deal was inked. At Zion, Rodda would supervise the manufacturing of Sparkling Gems hard candy and Dove Brand cream chocolates. Rodda’s time in Zion only lasted two years, because financial trouble with the other industries made them shut down the candy operation in 1904 with lack of cash flow to buy raw materials, even though it was the most profitable business.

Around 1903, Dowie really went off the deep and and took on a persona of Elijah the Restorer, messenger of the Second Coming of Christ, much to the dismay of many of his followers. He was soon trotting around the globe in an Old Testament prophet costume of his own design, with patriarchal headgear, jeweled breastplates, and an ornately carved shepherd’s crook. This was great for a costume ball, but probably not as great for the credibility of the leader of America’s largest cult. He began endangering an otherwise promising Christian socialist experiment by borrowing against Zion’s already waning assets. Dowie was doing this to leverage an even more ambitious utopian initiative called “Zion Paradise Plantation,” a million acre agricultural commune he proposed to establish in Mexico, to supply the cotton, sugar, and other supplies needed for the industries in Zion City, Illinois. It would be manned by African converts who were “suited to working in the harsh environment.” Cincinnati opera cream inventor Robert Putman, and the Cincinnati Zion Deacon, W. B. Yerger, a rich Cincinnati insurance owner, met Dowie in Cuba in 1905, and went with him to Mexico to meet with Mexican President, General Porfirio Diaz, who had held a strong hold on Mexico for nearly three decades. Other Zion officials would meet them to discuss the project, which never came to fruition.

By 1905, Rodda was back from Zion, involved in Cincinnati candy companies, as a partner in the Reinhart & Newton Candy Company. And then in 1907, living in Norwood, he partnered with Robert Putman in his candy business, which amounted to three stores, one of them in the Fair, a large department store at 6th and Race downtown, that had its grand opening in 1906, at the height of the Dowie scandals.

In 1906, Zion elders were concerned with Dowie’s ability to lead the congregation and his lofty plans. They recalled Glenn Voliva from Australia, ousted Dowie by letter to Mexico, and instilled Voliva as the new leader of Zion, making him owner of all of Zion’s assets. The assets of the Cincinnati Zion community were transferred immediately to Voliva as well. Glenn Voliva had originally been a preacher of the Disciples of Christ in Washington Courthouse, Ohio, before hearing of Dowie and converting to his cult in 1899. Dowie sent Voliva to be the leader of the Cincinnati community for 8 months from 1900 to 1901. During that time he increased the flock there from 100 to 400 congregants, many of whom were recruited from workers at Putman’s candy factory. While in Cincinnati, in 1900, Voliva’s son, Paul died after four days of intense suffering of spinal meningitis, without the care of physicians. The Cincinnati coroner investigated the incident and Voliva thought he was put through the ringer for the affair. Voliva had his son buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, and then was sent to Australia to help the Zion congregation there.

By this time, Dowie’s wife and son had moved out of the Shiloh house mansion in Zion, and there were rumors they were divorcing. There were also accusations that Dowie had preached polygamy and had a love affair with a young Swiss congregant who lived with them at Shiloh house for a brief period. Many had made accusations that both Dowie had taken advantage of followers’ funds and led a lavish lifestyle, driving the community and its industries towards bankruptcy. Not surprisingly, Voliva, later in life would admit to leading a lavish life on the finances of his followers. In the midst of all this, Dr. Dowie died in 1907 at Shiloh house, without his wife and son.

Putman had sided with the Dowie faction of Zion, while Rodda thought Voliva the better leader, and so the two split their candy partnership. After leaving Cincinnati during the controversy of Voliva and the Zion Church, Rodda incorporated his own Rodda Candy Company, and moved to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Rodda took the Sparkling Gems brand name from Zion for his own company, and when Zion Candy reopened their business they would rename their brand Sparkling Beauties. He severed his ties forever with the Zion church. In Lancaster, Rodda bought the American Caramel Company, which had bought the Lancaster Caramel Company in 1900 from an unknown candy maker named Milton Hershey, who wanted to get into the chocolate business.

Rodda merged the American Caramel company into Reinhart & Newton, which in turn had bought Cincinnati company, Dolly Varden, (maker of chocolate cherry cordials and other bon bons) and both operations were shut down in Cincinnati, in 1926. This shutdown caused a lawsuit by a large Dolly Varden shareholder, and wealthy Walnut Hills widow, Bertha Ruehl Selbert. Litigation would follow Rodda with his former business partner in the American Caramel Company too – a case that lasted nearly a decade.

It was about the late 1930s that Rodda invented the Marshmallow Peep. Originally it was piped out by hand by female candy makers and originally each had two little wings. Because of their delicacy and lack of shelf stability, it is thought that they were only made seasonally for Easter and for the local market, rather than distributed like Rodda’s other candy. Sam Born bought the company in the 1950s, automated the Peep process, and clipped the original wings offs each chic and brought it into the national candy spotlight.

Putman continued on with his business, making enough money to build a mansion in Ft. Thomas, Kentucky, on Mt. Pleasant Lane for his two spinster sisters. But his family was not done with their Zion connection. In August, 1911, his wife, Margaret Ward Putman, decided she wanted to help get Zion out of bankruptcy and take over the Church from Voliva. Several newspapers blazoned the headline “Woman to Burnish Zion: Mrs. Robert Putman of Cincinnati Opens Coffers that Dowiesm May Shine – Installed as a Priestess. The new figure who is expected to assume a position of leadership is Mrs. Robert Putman, a wealthy Cincinnati society woman, who has become so imbued with the teachings of Zionism that she is sad to have renounced a high social position and a host of friends to take up work as a leader of Zionists at Zion City.” She was going to use her money to return Zion to its Dowie Days of glory. She was also noted as the founder of the Cincinnati Zionist congregation. But Voliva was not going to let a woman take over his

The Putmans shared a tragedy with the Dowie’s. They both lost their only daughters young. Putman’s daughter Margaret died as an infant, and they never had any more children. Mrs. Putman rented a house in Zion and moved there to set up shop, but was unsuccessful in overthrowing Voliva. She died in 1922 in Zion, and her husband passed there too in 1928, but both were carted back to be buried in Spring Grove Cemetery.

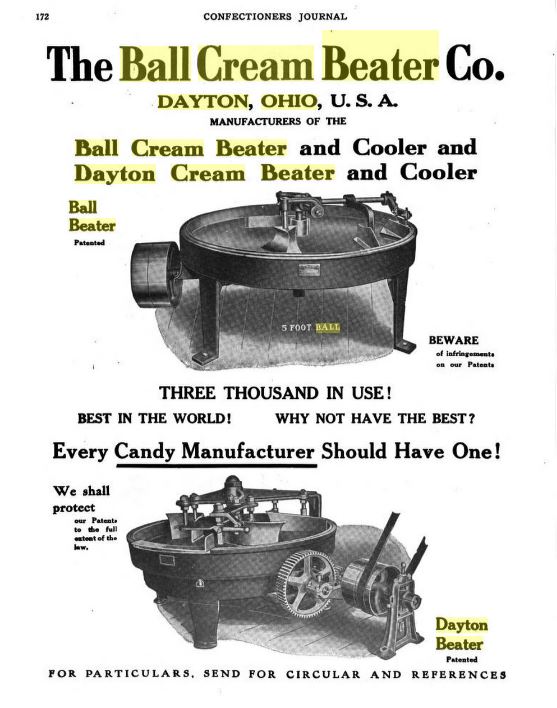

Their nephew Thomas Lykins took over their candy business in Cincinnati, continuing the tradition of making the famous opera creams. By this time, Papas, Bissingers, and a host of other Cincinnati candy companies had pirated the recipe (and purchased a Ball Cream Beater) and were making opera creams. The Putman brand is now owned by the Papas company, which still makes their branded opera creams. Papas, unfortunately, falsely takes credit for its invention –another stolen opera cream story!!

Zion today is a no longer a religious community and the original candy factory is no longer standing, having been demolished in the 1980s. Halal and Mexican groceries dot the outside of the town, and farms on the outskirts still supply beef for the area’s famous beef bacon. Dowie’s Shiloh house has been restored and now houses the Zion Historical Society. I visited the Shiloh house in February and got a rare after hours tour from the guide. I filled her in on the Rodda and Putman candy stories, and saw some of the candy artifacts of Rodda’s time running the factory. After Rodda left, the Zion Candy factory and bakery reopened in a few years and became famous for their Fig Pie Candy Bar and Fig Newton Cookies. There is still a bakery in Zion that makes the Zion brand fig newtons, along with Zion Dutch apple newtons, both of which are delicious. They’re available around Zion at Piggly Wiggly markets, the last legacy of the Rodda’s Zion Candy industry.

One photograph on the second floor of the Shiloh house shows evidence that Rodda might have known how to make the opera cream from his association with Putman in Cincinnati, and taught his candy workers in Zion how to make them during his tenure there. An early shot of the inside of the Zion candy factory shows a worker operating what looks like a ball cream beater, the same piece of equipment that makes the filling for our opera creams. But they called them Dove Brand Cream Chocolates, because, after all, Zion was a religious town, and the opera was just too secular.

Oddly enough, there is also evidence that Cincinnati had a distribution center for the Zion Dove Brand Chocolates and other products made in Zion. In the 1890s there were hundreds of neighborhood social beneficial organizations called, in German, Raucher Casinos, or Smoking Casinos, that met several times a month as a sort of social insurance agency. They smoked their porcelain German pipes, drank German immigrant beer, gambled on cards, (all prohibited in Zion) and donated a monthly due for sick pay and a death benefit before corporations offered sick leave, workers compensation and insurance. Of the many of these organizations that were incorporated in Cincinnati in the early 1900s was one called the Dove Brands Smoking Casino.