A self portrait of Duveneck painted in Munich, and his beloved Max Emanuel Café.

We all want that local hangout where we can meet friends and enjoy life over a pint of good lager bier. For our beloved local Germanic artist, Frank Duveneck, that hangout, while he was studying in Munich at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts, was a place called the Max Emanuel Café, or just MaxE by the new 20 something hipsters who hang there, 150 years after he and his artist buddies did. It’s in the heart of the Bohemian university district at 33 Adalbertstrasse.

If you go to Munich, ditch the loud touristy Hofbrauhaus and stop here first, to take in the legacy of one of America’s greatest painters and our hometown favorite. Duvie is sometimes called the Father of American Painting, and was loved by both his contemporary artists and his students. He was a virtuoso of the brush, but also a guy’s guy -the kind you’d want to get beers with and talk for hours.

A Duveneck Stammtisch, or reserved table at a pub, was something that he followed his whole life. Contemporary books, like Indian Summer, and others immortalize him as the lion headed king of beer hall post painting discussions.

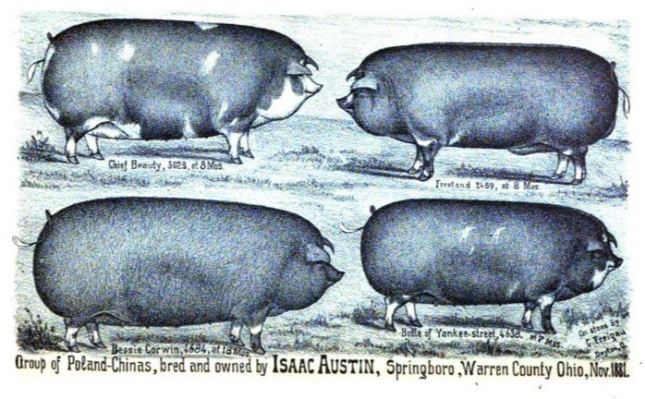

Born to Westfalian immigrant parents, Bernard Deckers and Katherine Siemers in 1848 in Covington, Kentucky, Duveneck was raised and adopted by his stepfather Joseph Duveneck, after his father died in his infancy. The Deckers were from Goetta country, from the area of Damme, right next to Neunkirchen Voerden, where the Finke family – who brought goetta to Northern Kentucky in the 1870s, immigrated. Joseph Duveneck was from the small village of Vibeck in Oldenburg, also in Goetta Country.

Joseph Duveneck and a partner, Henry Wichman bought what was the Hone Brewery in 1861 at the northeast corner of 12th and Stevens in Covington. It had its own beer garden in a lot next door where members of the Covington German Community congregated. Joseph was a member of the West End Covington German Pioneer Verein. The senior Duveneck operated the brewery until the end of the Civil War in 1865, so young Frankie grew up around this beer hall spirit of German gemutlichkeit. But by 1861, at age 13, Frankie was already apprenticed to an altar company and was travelling to Indiana, Pittsburgh, and Canada to paint the religious mural interiors of Catholic Churches. It was this early detection of his brilliant talent that got Duvie, through Cosmos Wolfe, a funder to travel to Munich to study at the Acadamey of Fine Arts in 1870.

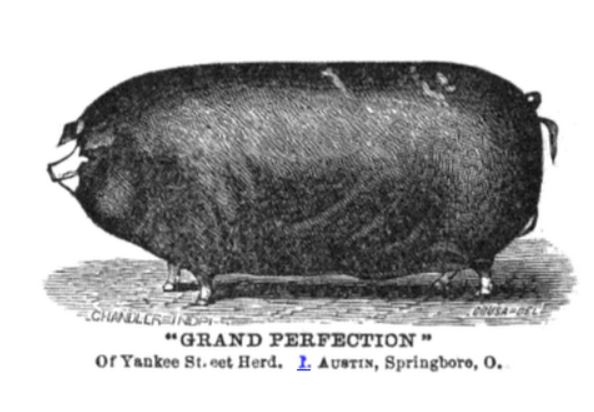

Elector and Ruler of Bavaria Max Emanuel.

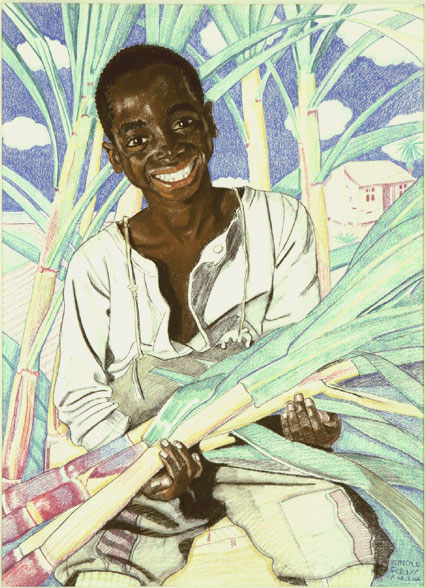

Duveneck studied under Wilhelm Diez, who emphasized study of Dutch and Flemish masters. Those that attended the Academy in Munich from 1850 to 1918 were taught in the Munich Style, characterized by a naturalistic and broad brush stroke and dark chiaroscuro, a deep contrast between light and dark. Duveneck studied there from 1870 to 1873, and then returned from 1875 to 1878. It was in Munich where he mastered his own masculine broad brush style in such famous paintings as Smoking Boy (1872), a version of which is now a larger-than-life mural on the side of the Red’s Stadium.

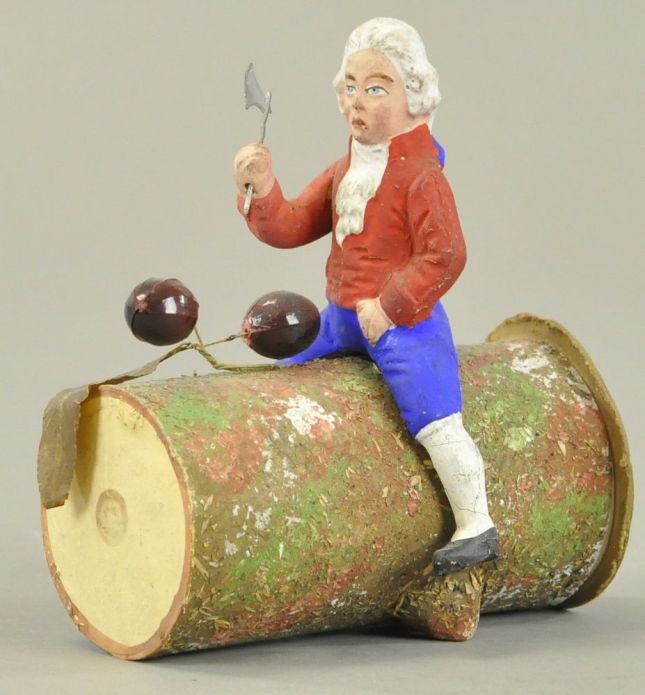

So why would Duvie and his buds choose Max Emanueal as their hangout of choice? Max Emanual, after whom the bar is named, was an avid patron of the arts. As ruler of Bavaria in the mid 1600s and one of the seven electors of the Holy Roman Empire, before Germany was unified. He was also governor of the Spanish Netherlands, and with this access amassed a large collection of Dutch and Flemish paintings, by such masters as Peter Paul Rubeens, Albrecht Durer, and Van Dyck, among others. This collection, now known as the Witteslbach collection was, in Duveneck’s time and today, on view at the Alte Pinakotehech Museum in Munich. That museum is also the only museum in Germany where you can see a Leonardo da Vinci, the Madonna of the Carnation. It was these paintings that Duveneck’s teacher, Herr Diez, encouraged his students to study and emulate in their own paintings.

Today Max Emanueal Brauerei still caters to the under 20 crowd, as it did in Duvie’s day. It hosts a weekly Salsa Dance Night, an annual White Party, has a nice outdoor beer garden, and is dog friendly. It serves Lowenbrau beer and a variety of schnitzel, ox knuckle, and other Bavarian standards, a far cry from the radishes and bretzels of Duvie’s day. Unfortunately it has been renovated many times in the last 150 years, but if you go inside and close your eyes you can imagine hearing Duvie talk for hours about his ideas on painting.

After the tragedy of losing his young wife, Elizabeth, Duveneck returned to Cincinnati where he taught at the Art Acadaemy from 1890-1919, teaching hundreds of both commercial and fine American artists. His true influence across American design has not been truly recognized. He continued the tradition of post painting Stammtisch. He and others at the Academy formed the Cincinnati Art Club, so they could paint female nudes, a practice not condoned at the Academey. Their first meeting spot was Hager’s Café on Walnut Street at 9ths. One of Duveneck’s female nudes hung infamously over the bar at Focoult’s Café in Over-the-Rhine.

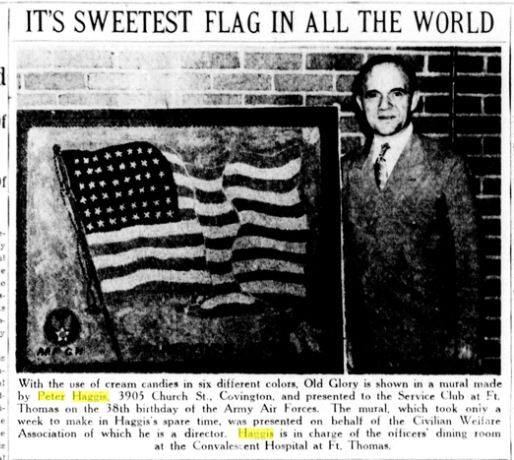

A contemporary Stammtisch at the Biergarten at Max E in Munich – the next generation of Duveneck Boys?