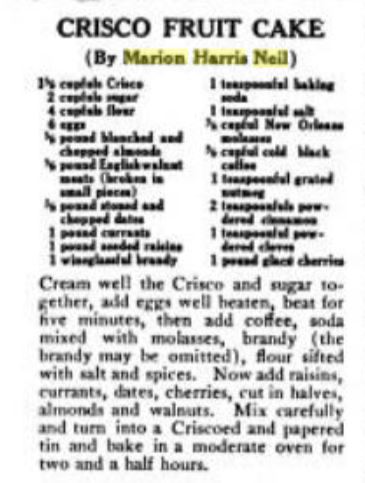

Vineyards in Cincinnati, along the Ohio during the Catawba Craze. Note the woman is carrying the larger load and her husband seems to be barking her orders.

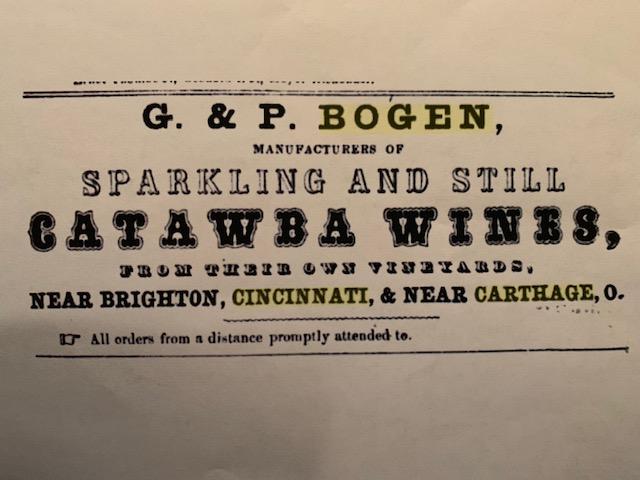

The more I dig into Cincinnati’s native wine heritage, the more I find these ghost towns that popped up around the Catawba Craze of the 1840s and 1850s. San Francisco had its Gold Rush, while Cincinnati had its Catawba Craze This was when Nicholas Longworth influenced poor Rhineland, Alsatian, and French/Swiss farmers to immigrate and become his tenant vine dressers. In the end, the tenant farmers, like the San Francisco miners, were the ones who were most taken advantage of. It was the brokers, distributers and retailers (German coffeehouse owners in Over-the-Rhine) who made the most out of the Catawba craze. And Longworth’s great Catawba experiment failed.

Nicholas Longworth died in 1863 before he was able to implement a cure for the phylloxera and black rot caused by our weird river valley climate. His son-in-law William J. Flagg wrote a great manual on how to cure black rot and prevent phylloxera infestations, but by 1863 after several bad weather seasons and decimated vineyards, none of the poor tenants or farmers could afford to continue to invest in their fickle native grapes. And most were at wit’s end with the fickleness of our native grapes.

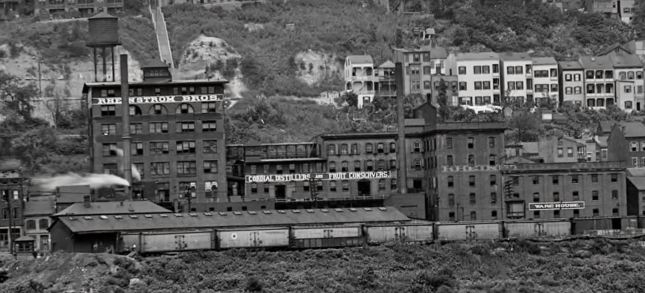

And others like Mr. Campbell of Delaware, Ohio, grafted and created more resistant stocks. Those that still wanted to tackle winemaking moved to Lake Eire and Pennsylvania where Concord and other more resistant native grapes were being grown. Longworth’s wine makers – James and Joseph Musson, from Rheims in Burgundy, went on to the East to develop champagnes and vineyards after Longworth’s grandson William P. Anderson sold the Longworth Wine House and began selling off the vineyard land in 1869. And the small farms – which was most of the 250 or so vineyards in Cincinnati – replaced their grapes with corn, wheat, tobacco and hay, which were more weather tolerant and profitable.

Another of these Catawba ghost towns was located at about where Guardian Angels School is on Beechmont Avenue in Mt. Washington. It was a small hamlet of farms called Brachman – named after German immigrant Henry Brachman, from Nordhausen, Prussia. He owned a 99 acre farm with a vineyard planted in Catawba grapes that spanned both sides of Beechmont Avenue between Beacon Street and Burney Lane. Brachman Street in between the two is where the family farmhouse was.

While Nordhausen is not really wine country, Brachman was married to a bit of an American wine legacy, Rosalia Bettens, who was born in Vevay, Indiana. Rosalia was daughter of Phillip and Rosalia Bettens, who were the leaders of the first 16 families from Vevay, Switzerland to immigrate in 1801 to found Vevay, Indiana. They were all vine dressers and winemakers, and were the first in America to successfully make wine out of native vinus labrusca, specifically the Alexander grape. So, Brackman had a free vineyard consultant in his father-in-law, and a wife that knew how to dress and care for vines. Longworth himself even admitted that it was the wives and daughters of his German immigrant tenants who did most of the hard labor in his vineyards.

Nicholas Longworth visited the Swiss winemakers in Vevay in the 1820s when he started getting interested in winemaking with native grapes on his land in Cincinnati. He invested heavily in the Catawba grape, that was supposedly more tolerant to black rot and pests, but it proved not to be. Longworth planted his first vineyards in Delhi on the West side in the 1820s, and set up immigrants Ammann, and Tuchfarber to terrace the hillsides and care for the vines. This sparked several other independent Germanic immigrants to grow grapes for themselves and the Longworth Wine House.

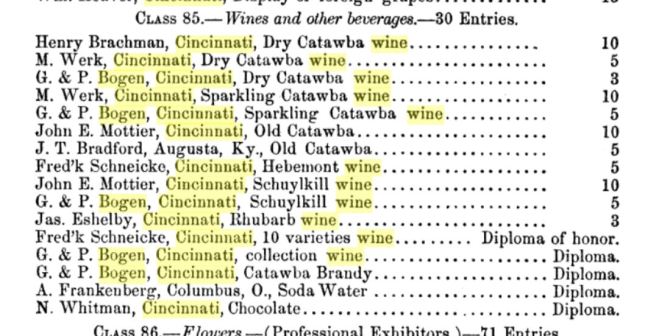

Brackman was one of the many immigrants who caught the Catawba Craze. In 1859, he showed his Dry Catawba Wine at the Hamilton County Fair, along with some of Nicholas Longworth’s tenant farmers like Christian Friedrich Schiecke, whose 18 acres of vineyards were part of Longworth’s Garden of Eden that went up into the Mt. Adams hillside from his house, now the Taft Museum.

Brachman was active in the Cincinnati Horticultural Society and the American Winegrowers Association. While being a farmer and a winemaker, Brachman was also a bit of a politician – serving as an Ohio Senator from 1862-1864. He was quite successful in enterprise as in 1873 he started the Cincinnati, Georgetown, and Portsmouth Railroad, a narrow gauge railroad that connected the farms of Anderson township and Clermont County to downtown. We might even call it the Catawba Choo-Choo. Brackman was able to sell the farmers to turn over their land for free for the right-of-way, with the promise of having a convenient daily route to bring their farm products to Cincy and Northern Kentucky markets. The railway operated until 1935, and its remnants can still be seen in California Woods off of Kellogg Avenue, which is where it descended the Eastern hillsides into Cincinnati. The railroad connected the vineyards of the immigrant winemakers in California, Five Mile, and another Catawba ghost town, Sweet Wine (called Wineburg, by the Germans), near Coney Island, founded in 1854 by Franz Helfferich, a founding member of the Cincinnnati Turnverein.

The immigrant wine growers of Sweet Wine had a connection with Stepstone, Kentucky, across the river, as they went to the St. John German Lutheran Church of Stepstone, which was the closest local Lutheran Church. Stepstone, Carntown, and neighboring Camp Springs (Four Mile), Kentucky were also enclaves of wine growers from the winegrowing regions of Germany – Baden-Wuertemburg, Rhinepfalz, and Switzerland. The Immaculate Conception Catholic Church of Stepstone, Kentucky was formed by early wine country Germanic immigrants, who had originally come to Cincinnati.

While Brachman did get to see the success his narrow gauge railway provided for the farmers of Eastern Cincinnati, it did not stop the end of the Catawba Craze. The hamlet of Brachman was soon annexed into Mt. Washington, and its history almost lost as it became, like many others a Catawba Ghost Town.