Every Memorial Day Weekend in Cincinnati, there’s an arrival of a very mysterious group at Spring Grove Cemetery. There’s both discretion and respect around their arrival, but the folklore about them runs high and has created a fascination of their customs with outsiders, especially with reality shows like My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding. This is the arrival of the Gypsies, or more accurately, the Scottish Travelers, who make a yearly pilgrimage to adorn the graves of their families with a multitude of over-the-top flower arrangements. It’s a tradition that supposedly has been going on for over 100 years. And, it started because of the generosity of the operators of Spring Grove Cemetery.

The Scottish Travelers, who are related to the Roma gypsies of Eastern Europe, had been coming to Cincinnati since around the time of the Civil War, on their way north in their summer east coast migration. They made their camps near the Cumminsville/Northside area on the Mill Creek, circling their wagons around campfires. The story goes that during their travel through Cincinnati in about 1890, a young child of the gypsy camp was struck and killed by a streetcar. The gypsies asked Spring Grove to hold the child’s body until they could return and pay for a proper funeral. The managers of Spring Grove agreed and the clans have been coming back ever since, burying their families at the cemetery, with rose colored granite tombstones and adorning every year with themed flower arrangements. They range from Elvis themed, to shapes of favorite consumer products or foods the loved ones enjoyed in life. The arrangements costs hundreds to thousands of dollars.

There are two deli products that harken back to the campfire days of these gypsy migrations. They’re not as common in Cincinnati, but can be found at mostly Hungarian or Eastern European meat markets, in Cleveland or Chicago, or other areas where Eastern European immigrants settled. The foods are called Gypsy Ham, szynka Cyganska , and Gypsy Bacon, Boczek cyganski. In America, the German version of gypsy bacon is called Zigeunerspeck.

Gypsy ham gets its name from its roots in gypsy camps where pork meat – usually the leg – was smoked over an open wood fire, giving the skin a darker color. The fat was taken off the leg, netted, and then smoked.

Gypsy bacon is seasoned with garlic and paprika, and then cut and skewered so it can be easily held over an open campfire. Once cooked, it is placed on a slice of rye bread with red onions and baked beans for a gypsy bacon sandwich.

Whether their names are considered politically incorrect or disrespectful today, these products have kept their origin story intact. So now we can celebrate these groups with their food.

Holtman Over-the-Rhine’s Maple Bacon on Blueberry Cake Donut.

I have a soft spot in my heart for baking families, as my mother’s family were bakers. But thankfully, I don’t have a soft spot in my enamel, at least this visit. The last thing you think you’ll learn about in the dentist’s chair is the legacy of Cincinnati’s hippest donut empire. Well that’s exactly what happened to me when I recently made my twice yearly cleaning appointment. Little did I know that my dentist married one of the Holtman donut family, whose Over-the-Rhine donut shop has a line snaking down Vine Street almost any weekend morning.

The conversation was a bit one sided. It’s kinda hard to carry on a conversation when a stainless steel scraper is spanning your mouth. But it all started with a discussion of local restaurants that offer live music. My dentist told me about his 80-something year old father-in-law, who still plays the saxophone, and goes out with he and his wife on the weekends to listen to bands, sometimes making a cameo appearance on stage.

This saxophone-playing octogenarian is none other than the oldest living original Holtman donut brother, Marvin Holtman Jr. His brothers Charles and Roger Holtman started Holtman Donuts in 1960 in Newtown, Ohio, to give their father Marvin Sr,. a job after he had lost his as a milk delivery man. Marvin Sr. opened a second location in Milford in 1964. Then, as other family members saw the success, they opened multiple locations in Cincinnati.

Marvin Jr. was one of those other family members, who operated two Holtman Donut shops in Norwood, one at Smith, and one Allison Roads near the baseball field. That’s where my dentist met his wife, Marvin’s daughter, even though he was not a donut fan himself. I wonder how many of my dentist’s patients are loyal Holtman eaters.

Another family member who branched out was Charles Hotlman’s daughter Marcella Holtman Poole. She opened Marcella’s Bakery, recently passing it on to her daughter, Carmen Meholick, and Carmen’s son, Tristin Meholick, who now manages the Amelia, Mt. Carmel, and Eastgate locations. The 21 year old is passionate about growing the business. He’s landed an account with the Hotel Covington and has released his version of the New York invented cronut – the croissant-donut love child.

Fourth Generation Holtman descendant, Tristin Meholick, owner of Marcella’s Doughnuts & Bakery.

Marcella’s sister, Toni Holtman Lazarin, is the current keeper of the original Holtman donut recipes. She and sister Marcella are two of 10 children of Charles Holtman, all of whom learned to make the signature hand-cut Holtman donuts. Toni and husband Chuck run the Loveland and Williamsburg shops, with help from other family members, while Toni’s son Danny Lazarin and wife Katie are the ones who opened the super-popular Over-the-Rhine location in 2013.

The Holtman Donut Family.

In addition to the traditional Holtman donut recipes, the Over-the-Rhine location offers specialty pastries like the sufganiyot, a deep fried jelly filled donut available during the Hannukah season. They also make a completely decadent maple bacon-iced blueberry cake donut. My sister bought Holtman’s oversized donut cake for one of my nephew’s birthdays and its delicious.

It’s so worth the wait in line for a Holtman donut if you are ever tooling around downtown on the weekend. But make sure you brush after eating!

The Nasty Nata from Nando’s in Chicago – a Portuguese Nun-invented egg custard tart.

Last night in Chicago, I was looking for a quick, but good meal on the way to see Hamilton. I found one of the few international fast casual chain that we’ve actually imported. America has certainly exported our quick service chains overseas. It’s a chicken joint called Nando’s that features a spicy sauce called Peri Peri used on grilled chicken, and it’s cuisine is African-Portuguese. The seemingly fusian food comes from a time when Portugal owned the high seas, and had a colonial influence during the 15th and 16th centuries, that spanned, India, Africa, Asia, and South America.

Peri Peri sauce originated in Mozambique. But the chain originated fairly recently – in 1987, when Portuguese born Fernando Duarte and Robert Brozin bought a South African chicken place called Chickenland that served the grilled chicken with peri peri, in which their now 1000 world locations specialize.

After a wonderfully spicy peri peri chicken leg with spicy brussel sprouts, I had to try one of what they call their “Nasty Nattas,” a small egg custard the size of a silver dollar that they serve warm with cinnamon and sugar.

The pastry is based on a Portuguese pastry known as ‘Pastel de Nata’ that was created by nuns at the Convent of Santa Maria de Belem outside of Lisbon. In convents and monasteries, egg whites were used to starch clothes, especially nuns’ habits. So they had a lot of leftover egg yolks that they used to make the pastries to give to visitors and sell to support themselves. This led to an entire industry, still strong today called, ‘dorcaria conventual,’ pastries made in convents. There are others – like one called barrigia de freira – or nun’s belly. The Portuguese wine industry also created a bumper of unused egg yolks. It was found that using egg whites as a filtering agent for wine was very effective. So the winemakers also had cheap egg yolks to supply the convents and bakeries.

The particular Pastel de Nata has been made continuously on the same site in Lisbon since 1837 and is a huge hit with locals and tourists alike. Nearly every corner in Portugal has a bakery that makes its own egg custart tart.

Lots of the pastries have sort of cheeky nun names that point to the reason Nando’s calls theirs the Nasty Natta. Even though Portugal’s Catholicism was a mix of Muslim, pagan, and devotional beliefs that was perfect for subjugating women – love ruled Portugal. It was a culture of contradictions. Women wore a face veil similar to Muslim women and weren’t allowed to travel in public without escorts. Women caught conversing on church steps could be imprisoned. But even married women and nuns found lovers. So many men fell in love with nuns in Portugal – there was a term invented for nun lovers – “freiraticos.” These men seemed not to see the irony of subjugating their wives, but falling in love with nuns over whom they had absolutely no control.

A 2006 book called Letters from a Portuguese Nun, by author Myriam Cyr, documents one of these love affairs.

I was happy to have a tasty, but naughty, sweet ending to my spicy peri peri chicken whose history spans back to 16th century nuns.

Where else but in Cincinnati can you get a great malt at a gas station convenience store? I’m talking, of course, about any of the 200 locations of UDF, United Dairy Farmers. As the warm weather is finally upon us, our minds turn to cooler thoughts like ice cream. I’ve always taken for granted the ready availability of a UDF malt. UDF has only been around since 1943, when the Lindner’s decided to undercut all the milk delivery businesses in town, by selling direct. But Cincinnati soda fountains served ice cream shakes and phosphates from about the 1880s onward.

Malt is basically a powder made up of malted barley, wheat flour, and evaporated whole milk. It was the original energy drink. Early in its origin story, malt was used as a health food for infants and invalids. English pharmacist James Horlick had developed this formula, and in 1873 started a company in Chicago with his brother, William, to sell their malted baby food. In 1883 they earned a patent for a malt formula fortified with dried milk.

Horlick, the inventor of malted milk powder.

It quickly found another market. Explorers appreciated its lightweight and stable qualities, as well as its high caloric content, and made it their provision of choice, on their treks around the world. Horlick’s even sponsored the Byrd expedition in Antartica.

Plain malted drinks without ice cream, like Carnation and Ovaltine are still around. Horlick’s original malt is still popular in India, where because of religious reasons, the drink is made from Buffalo milk instead of cow’s milk.

But how did the malt take the form that we see at UDF and other malt shops? Malted milk was a natural for the soda fountain. It was not only nonalcoholic but healthy. In 1922, Ivan “Pop” Coulson, a Walgreens employee, wanted to improve their chocolate malt beverage. Ivan was a soda fountain guru who was always experimenting with fountain concoctions. The original Walgreens recipe was milk, chocolate syrup, and a spoonful of malt powder. Coulson, with the addition of one ingredient – ice cream – would invent a form of the malt that would stand the test of time -the malted milkshake.

Americans loved the taste and turned a health food into a pleasure food, as it would later do with peanut butter and granola. And now, we have that brilliant soda jerk Ivan Coulson to thank for our delicious malts.

The Strietmann Biscuit Company in Mariemont.

In the warm weather months, when the wind patterns are right, I can sit on my front porch and smell a wonderful vanilla cookie smell from the old Keebler, now Kellogg factory in Mariemont at the foot of the Red Bank valley from my house. It’s a delightful summer bennie, and contrasts the garlicy grilled smells I get from the back porch of my house wafting over from Bankock Bistro and M.

My father used to be the account manager for the Keebler employee cafeteria at the Mariemont site, back when he sold commercial food programs, and sometimes he’d bring back some of their product samples from a customer visit.

What I have known as the Keebler bakery plant has actually been in Mariemont since 1943, and the company who built it, Strietmann Biscuit Company, has a history that goes back to just after the Civil War in Over-the-Rhine, when crackers were still known by their English name – biscuits. It was probably some time after World War I when Americans stopped calling crackers biscuits.

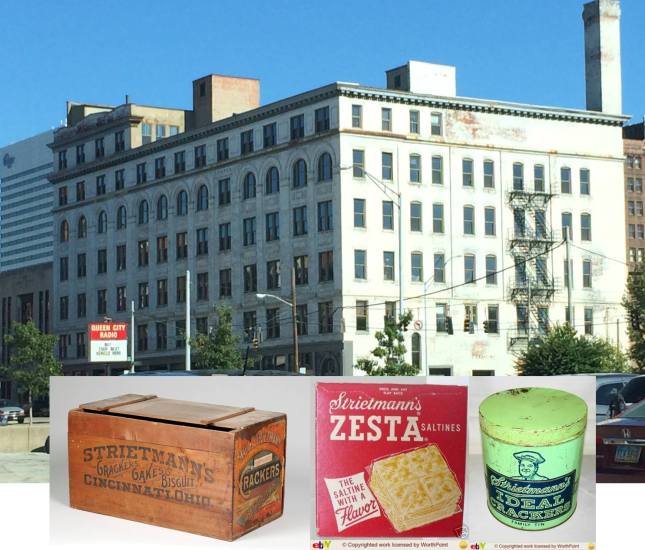

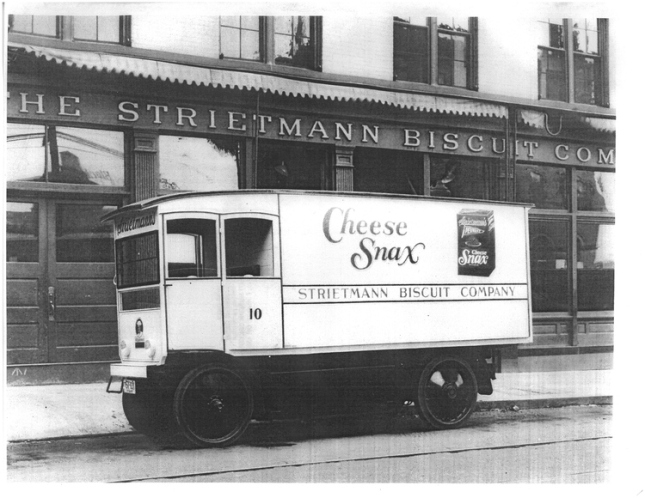

The original 1899 built Strietmann factory on West 12th street adjacent to the Miami and Eire Canal (now Central Parkway) is now being renovated into luxury apartments. The executive offices of that building were also used to pose as the New York Times offices in the new Cincinnati-filmed movie, Carol. The company was founded in 1873 by German immigrant George H. Strietmann, who was a member of the Cincinnati Turner Society, a German sport and social club that became a national movement.

During their time at the Over-the-Rhine facility, Strietmann produced a variety of crackers – the graham cracker, sugar wafers, a variety of snap coookies, pretzels, and a truly American common brand, Zesta soda crackers, which was adopted by Kraft as their national saltine cracker brand and sold by Kellogg today.

The 1899 Strietmann Factory in Over-the-Rhine and some of their original products.

One of the products that Strietmann also made was called Cheese Snax. The Cheese Cracker or Cheez-it was invented in Ohio, but not by the Strietmann Company. It was actually invented in Dayton, Ohio, in 1921 by the Green and Green Company (founded by Greenville, Ohio-born, Weston Green) on the corner of Cincinnati and Concord Streets. His company would later become Sunshine Crackers, which is now owned by Kellogg, who still sells the immensely popular Cheez-It Crackers.

The Strietmann Company became in 1927 a regional bakery division as part of the United Biscuit Company, along with Godfrey Keebler’s Philadelphia based commercial bakery, and several others. The Keebler Bakery was actually the first bakery in 1936 to bake Girl Scout Cookies. Before that the girls and their mothers did the baking.

In 1966, United Biscuit decided to choose a united national brand across all of their divisions and Strietmann became Keebler. In 2001, Keebler was acquired by the Kellogg Company, who owns the deliciously smelling Mariemont site today, and whom I have to thank for the summer vanilla cookie aromas.

Hmm

Today I got the email from Dutch’s sous chef that I had been waiting for over a week. Basque sausages are in! They had just been made this morning. I had till 9 at night to stop by my neighborhood charcuterie and pick up some of these delicacies.

I’ve been enamored with the Basque region since high school after reading, The Sun Also Rises by Hemingway. In the 1926 classic, he romanticizes the whole festival of San Fermin in Pamplona, Spain, where the infamous running of the bulls happens every July. I love the culture, the passion of the Basque people and their food. And, travel there is high on my bucket list. I want to see the Frank Gehry designed Guggenheim Museum in Bilboa, and I want to dance and drink at all the little festivals til the sun comes up.

So, if I can’t go to the Basque now, I’ll taste its flavors until I get there.

As the butcher who made said Basque sausages was talking me through their ingredients – roasted red bell pepper, pork, garlic – I stopped him at Espelette. What the hell is that, I asked? I had never heard of that one before. He said it was the pepper of the Basque region and the cornerstone of their regional cooking. It’s sort of like paprika, but has a subtle otherness that paprika doesn’t. He brought over the container of dried Espelette and let me take a whiff. There was definitely the smokiness of paprika, but there was a sweetness, and this other worldly sort of scent that was reminiscent of Grippos potato chip spice and a Vietnamese-Chinese sausage spice my roommate in college used to bring from home. It was exotic and lovely and I can’t wait to use them in a weekend meal.

My weekend scavenger hunt is to see if Colonel D’s at Findlay Market has Espelette. Hmm – I wonder how it would taste in Cincinnati chili?

The butcher at Dutch’s learned his sausage art, oddly enough, making the homemade meatballs and sausages at Mt Lookout’s Ramundo’s pizza on the square. I had no idea they made all their own.

Because this was such a clean and mild sausage, he recommended cooking it in hot water and olive oil – sort of like sous-vide and then give it a couple of turns in a pan or on a grill for the sear. He said the mistake most people make is grilling or searing a nice sausage at too high a heat, bursting the skin and letting all the flavors out.

So this weekend, I’ll break out my beret, some good Spanish wine, and cook some wonderful Basque sausage – all are welcome – just bring more wine!

St. Louis’ Chili Mac.

St. Louis and Cincinnati have a lot of food commonalities. On the pastry side, St. Louis has a gooey butter coffee cake, while Cincinnati has its cheese crowns. St. Louis has its own style of pizza, with its own type of cheese, called provel. Cincinnati has LaRosa’s pizza . And, when it comes to chili – or chile, as they spell it in St Louis – they have their own too, and they serve it on spaghetti, calling it chili mac.

St. Louis Chile is perhaps a bit older than Cincinnati’s. But unfortunately theirs is fading out, while Cincinnati’s is going strong, fueled by the two big chains Skyline and Gold Star. St. Louis chili was founded by two brothers (like Cincinnati’s Macedonian Kiradjieff brothers), Otis Truman Hodge (1872-1942) and his younger brother Mervin C. Hodge (1879-1952) around 1904, when Otis operated a food stand at St. Louis’ 1904 World’s Fair. He shortly thereafter opened Hodge’s Chili and Lunch Room at 814 Pine Street.

Otis Truman Hodge (founder of St. Louis Chile) and wife Miriam.

St. Louis Chile does not have a Macedonian or Greek heritage, like Cincinnati chili. John Eirten, great nephew of the founder, by marriage, says the predominant spice in their chili is cumin, and they use a fatty, more coarse ground meat, than Cincinnati chili does. It is also served in a few more creative ways than Cincinnati chili. St. Louis has chili topped spaghetti that they call Chile mac, and chili topped hot dogs, but they also have chili topped tamales called “tamale in”, something called the “Slinger” (a chili topped hamburger, hash brown, and fried egg mashup), and “Chili mac ala mode”, which is spaghetti, fried eggs and chili. A “top one” is a chili mac topped with a tamale. Two chili topped tamales is called a “21”. St. Louis’ much heartier variations morphed out of the diner culture, rather than Cincinnati’s chili parlor culture, and thus the addition of fried eggs, hash browns, and burgers.

By 1930 there were 17 locations of O.T. Hodge’s Chile Parlors around St. Louis, between the River and Jefferson Avenue. They, like the original Cincinnati Empress Parlor, spawned several others, but not anywhere near as many as Cincinnati’s 250 parlors. The atmosphere at an O.T. Hodge’s was the same as a Cincinnati chili parlor– a stool flanked counter and steam table with a few tables and chairs. And, you could find anyone from a judge to a laborer sitting side by side.

The last O.T. Hodge’s sadly closed in 2013, but Big Ed’s Chili Mac, which is also owned by a Hodge relative, John Eirten, is hanging on. Cincinnati’s last two Empress Chili Parlors, in Bridgetown and Alexandria are also barely holding on. Many people still have nostalgia for these longtime chili parlors, but changing demographics and economics of the neighborhoods caused many to close.

Harry Brunsen (1918-1998), husband of Otis’s daughter Ruth, was the last one to own an O.T. Hodge chili parlor. Early on a relative of Otis’s split and founded the company that would can and supply frozen bricks of chili. That business is still around today and supplies the chili that many diners use to top their many varietals of the St. Louis Slinger.

The original Bubbles can to the left, and the new can.

The craft brew industry has brought some great new innovation in beers and fermented alcoholic drinks, some that blur the lines between categories. Unfortunately these blurry, boozy new craft drinks have to be categorized by state law to be taxed correctly. That causes some confusion and problems, like what has recently happened with Rhinegeist’s new Rose Cider they call Bubbles. It’s bit of a unicorn in the craft brewing world.

Bubbles is primarily a cider – fermented with apples, but also with added peach and cranberry juice to give it that rose pinkish tone for visual affect and subtle flavor adder. However innovative and delicious the addition of the fruit juices make it, by Ohio Revised code, they also make it a wine, especially if the fruit juices are used in the ferment. That means that instead of the 24 cents per gallon tax, it now gets a 32 cents per gallon tax and would drive the price up and out of the increasingly popular cider market.

So, a collector’s item can has been created. At release the original Bubbles can said “Bubbles – Rose Cider with Peach and Cranberry.” That was until the state inspector saw it and now the can reads “Bubbles – Rose Ale.” I was at Amerasian Restaurant in Covington, Kentucky, last night and had a Bubbles with the original can – I should have kept it for posterity! Our server gushed at how much she loves Bubbles, when I ordered it.

This type of innovation of crossing lines between categories should be encouraged. These old Ohio codes, some pre-Prohibition, don’t reflect this brave new world of the craft brew. And, this exact experimentation of the last several hundred years, adding a little bit of this, a little bit of that, is how all the wonderful categories we enjoy today were developed.

Now Rhinegeist have made bubbles into an ale – I’m not exactly sure, how – but that means it actually gets less tax than a cider (now 16 cents per gallon vs. 24 cents) even though on Rhinegeist’s website, they market it as a cider in their “Cidergeist” group of three ciders. By they Ohio Revised code definition, to be levied as a beer (of which category an ale falls under) the beverage has to be brewed with a malt substance like barley, corn, rice, or wheat. Now that’s innovation! Cheers to Rhinegeist for making a superb winey-cider available for the price of a beer!

Nicholas Longworth, the Cincinnati Father of American Wine would be proud. He sold a crappy fortified, fizzy Catawba wine as a champagne and won a ribbon in France for it !!

It’s the day after I was first quoted as saying “bullshit” in print, for an interview with Munchies Magazine. I was passionately defending my beloved Cincinnati Chili. My expletive was in reference to all the naysayers from Texas who claim that Cincinnati has absolutely no claim to chili. Well, they have a little history lesson coming to them.

Cincinnati is in fact the birthplace of American chili powder. Of course, the spice of ground dried chilis was first invented hundreds of years ago by the Chili Queens of what is now Mexico for their chili. But the Queen City gave birth to the man who invented the modern blend of chili powder that ALL Texans and chili makers, even Cincinnati chili markers, use.

And oh yes, Texan chili historians will claim their own as the inventor. Texas historians claim that he was a Czech-German immigrant named Wilhem Gebhardt who landed in New Braunfels, the land of kolachis and jetronice (a cousin of goetta). He is purported to have invented chili powder in 1896. Gebhardt operated a café in the back of what was called Miller’s saloon. He invented a way to pulverize dried chilis into a powder that he called Tampico Dust, and then quickly renamed Gebhardt’s Eagle Chili Powder. Well that’s all fine and good, but it was probably more like paprika (a mild chili) because of his Eastern European origin, than modern chili powder.

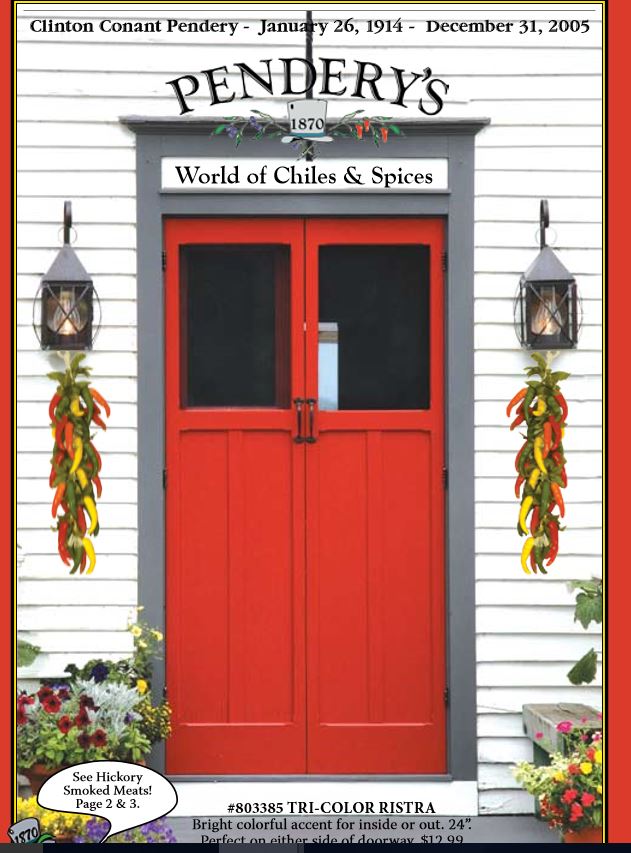

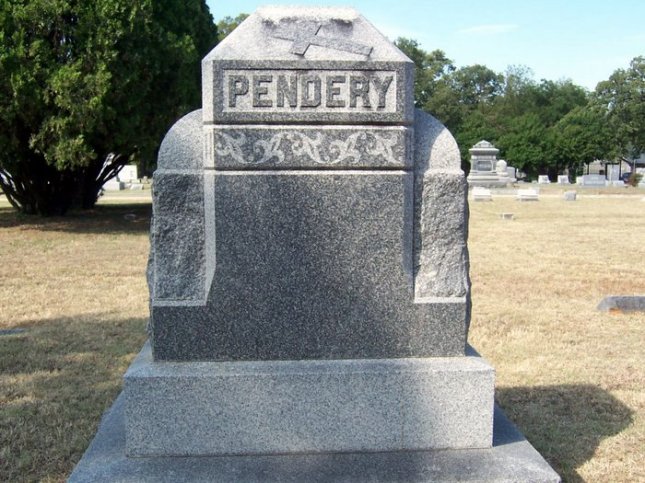

Rewind nearly three decades earlier to bustling Cincinnati. DeWitt Clinton Pendery (1848-1924) was itching to move west and join his two brothers at their successful dry goods business in Ft. Worth, Texas, blocks from the courthouse. All of DeWitt Clinton Pendery’s siblings were born in Cincinnati – Nellie, Anne, Thomas, Semiramis (love that name), Eugene, and Frank. DeWitt in 1870 took one bumpy ass stagecoach ride from Cincinnati to Ft. Worth, Texas, and joined his brothers in the trade. He arrived in the center of town and was nearly laughed back on the stagecoach because of his Yankee attire of his tall Cincinnati – made silk tophat and long frock coat. Legend has it that in true Wild West form, someone shot a bullet and grazed Pendery’s tophat in jest.

Pendery had developed an interest in spices. As a sideline to the dry goods business he began selling a spice blend of ground chilis, cumin, oregano, and other spices that he called Chiltomaline. The fifth generation of the Pendery family , Clint Haggerty, claims he started selling the chili powder at least around 1885, probably earlier, and cafes, restaurants, and citizens loved it. Sorry Gebhardt, that beats your late-to-the-game 1896 – copycat!! The Pendery family still sells the original Chiltomaline formula, along with hundreds of other spices from their catalogue and store.

Pendery’s family legacy in Cincinnati can be read through famous streetnames. You see, Dewitt was born in Cincinnati in 1848 to Ludlow DeMun Pendery and Catherine Sheppard. Ludlow Pendery’s parents were Alexander Pendery and Mary Ludlow, born in Cincinnati in 1791 to John Ludlow and Susan Demun. Now the names should start getting familiar. Mary Ludlow’s uncle Israel Ludlow, came to Cincinnati (or more accurately Ft. Washington, at the time) after the Revolutionary War, to survey the Symmes Purchase, out of which the City of Cincinnati was carved. By the 1870s when DeWitt Clinton Pendery left for Ft. Worth, there were many large spice companies in Cincinnati, where he could have been exposed to spice blends.

So chili and chili powder really do come to the core of Cincinnati. We could even say we taught Texans how to make their chili, or at least how to make their chili powder. Take that Deadspin!

The Memorial in Oakwood Cemetery in Ft. Worth Texas, to Cincinnati born, Chili Powder inventor, DeWitt Clinton Pendery.